Plateaus on Stronglifts 5×5 are inevitable.

- You can’t add 5lb on the bar 2-3x/week forever. It’s unsustainable and will eventually cause failed reps even if you deload.

- You can’t expect infinite strength gains by doing the same two workouts forever. They become less effective because your body adapts.

- You have to change the Stronglifts 5×5 program over time in order to break through plateaus and hit new personal records.

In this guide I’ll show you what plateaus really are, the three most common plateau mistakes people make, the real reasons why everyone eventually plateaus, and how to actually break plateaus on Stronglifts 5×5.

Let’s go.

Contents

Join the Stronglifts community to get free access to all the spreadsheets for every Stronglifts program. You’ll also get daily email tips to stay motivated. Enter your email below to sign up today for free.

Plateaus explained

What is a plateau

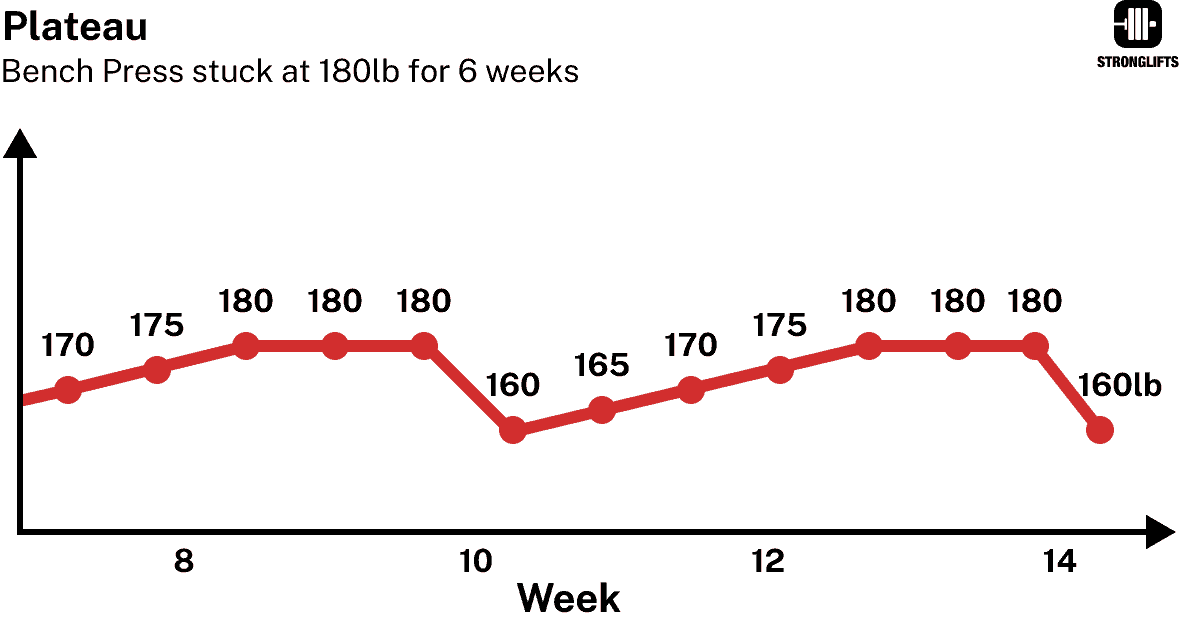

A plateau is when you’re stuck at the same weight for a long time.

You’ve been going to the gym consistently. You’ve been putting in the effort. Yet despite this you’ve been unable to progress. You’re still stuck at the same weight that you were lifting several weeks, or worse, months ago.

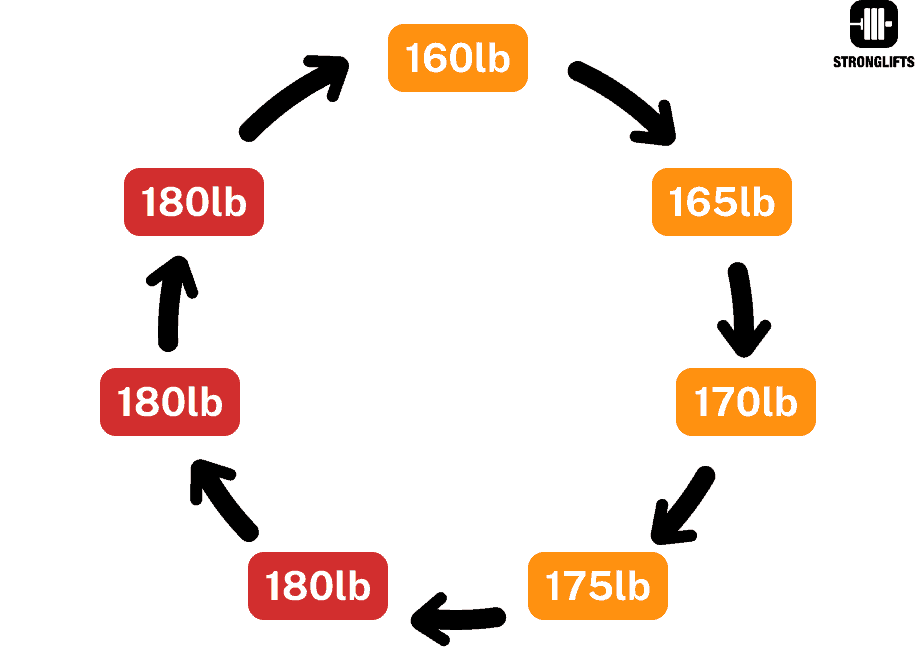

Example: you Bench Press 175lb for 5×5. Next workout you move to 180lb. You fail to lift it for 5×5. You try 180lb again next workout. You get a few more reps but still can’t do 5×5. You try one last time with 180lb next workout. You manage to do two extra reps but still fall short of 5×5.

You deload to 160lb. You’re back at 180lb after a few workouts. You fail to do 5×5 again. You repeat the weight for two more workouts but still can’t do 5×5. It has now been six weeks since you’ve been unable to get past 180lb.

This is a plateau.

Struggling is not a plateau

Having to put in more effort than before is not a plateau.

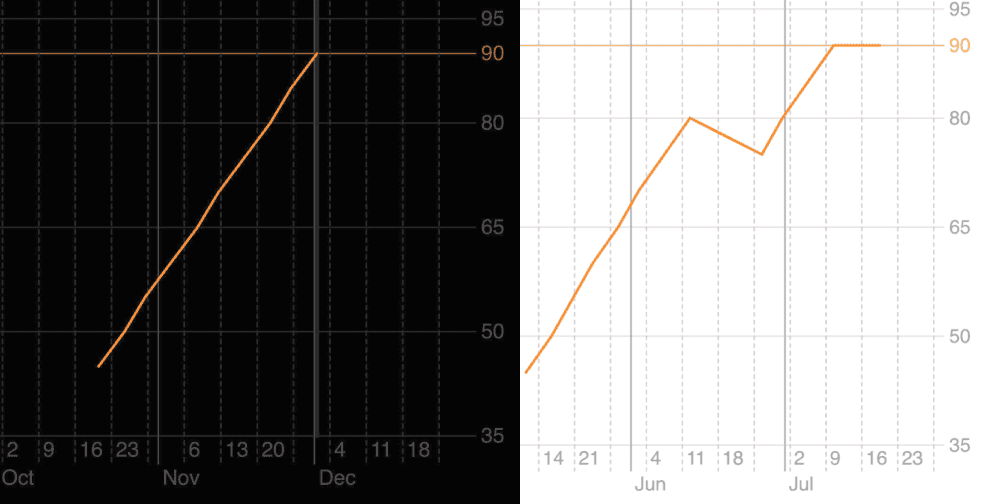

I get emails all the time from people saying they “hit a plateau”. It’s usually on the Overhead Press. I ask for a screenshot of their graphs in the Stronglifts app to look at their progress. Here are examples of what I’ve received…

These are not plateaus.

You lifted more weight this month than last month. You lifted more weight this week than last week. You lifted more weight this workout than last workout. None of this is a plateau. It’s consistent progress (*).

Why do they say it’s a plateau then?

- Adding weight on the bar has become harder. They have to push more to get 5×5. They have to rest longer between sets. They have to take bigger breaths to complete their sets. But this is not a plateau.

- They used to add 5lb every workout. Now they can’t complete 5×5 but fail reps. They have to repeat the same weight for a workout or two before they can add more on the bar. Not a plateau.

- They failed 5×5 with 200lb for two workouts in a row. The first time they did 5/4/3/2/2. The second time they did 5/5/4/3/3. They failed 5×5 twice but did four more reps the second time. Again, not a plateau.

- They were failing a lot with 5lb increments. So they bought fractional plates and switched to smaller jumps of 2.5lb. They’re no longer failing reps now but progress is slower than before. Not a plateau.

- The weight is starting to feel heavy on their back or in their hands. They’re feeling fear they didn’t have before. They find themselves doubting that they can do 5×5 with 5lb more, even though they keep surprising themselves. Not a plateau. Really.

Just because adding 5lb on the bar was easy for the past weeks, doesn’t mean it will continue to be easy forever.

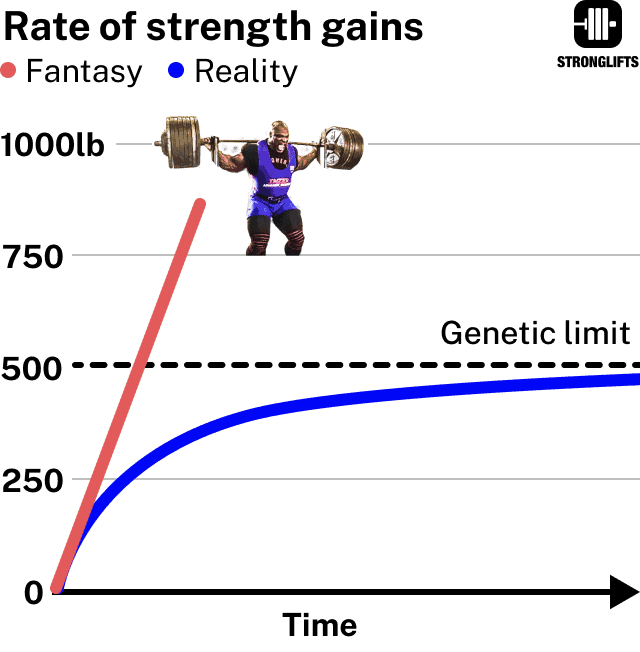

This is obvious if you do the math. Say you start with the empty bar. You add 5lb every workout, 3x/week, for 52 weeks. You get 5x3x52=780lb. Add the 45lb bar and you get 825lb in one year. That’s 374kg.

Do you see many people Squat 825lb in your gym? No. It’s a monster weight. This shows you that this isn’t not an easy weight to reach. If it was easy, then everyone in the gym would be Squatting 825lb. That’s not the case.

You should therefore expect your progress to slow down as the weight on the bar increases. Adding the same 5lb on the bar that was once easy will require more work and effort as you get stronger. This is normal.

Slow progress is not a plateau

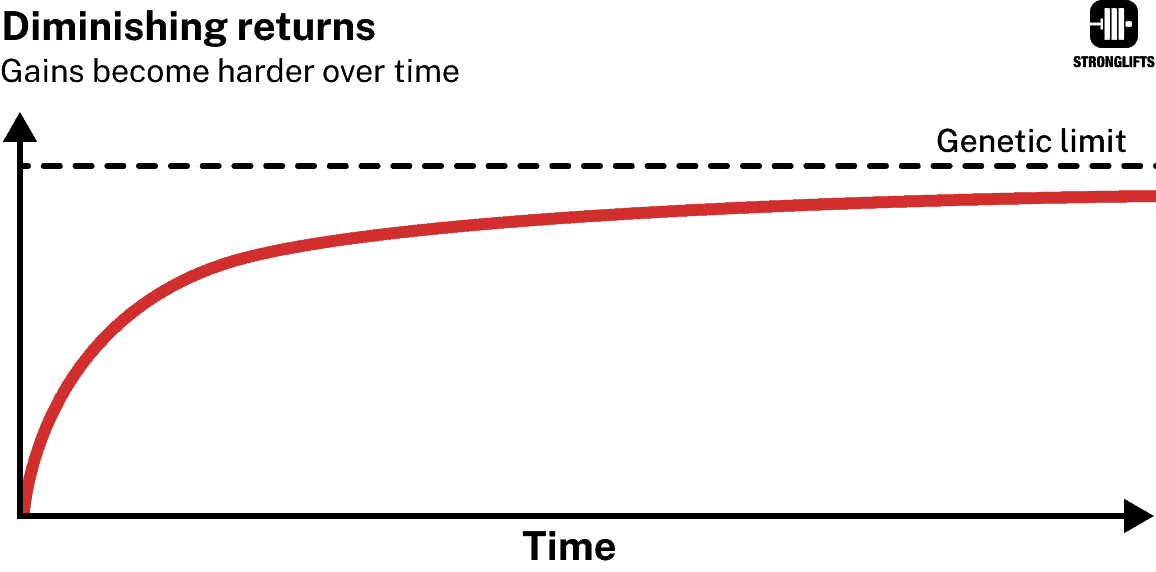

The stronger you become, the harder it is to become even stronger. Weaker lifters get stronger faster than stronger lifters.

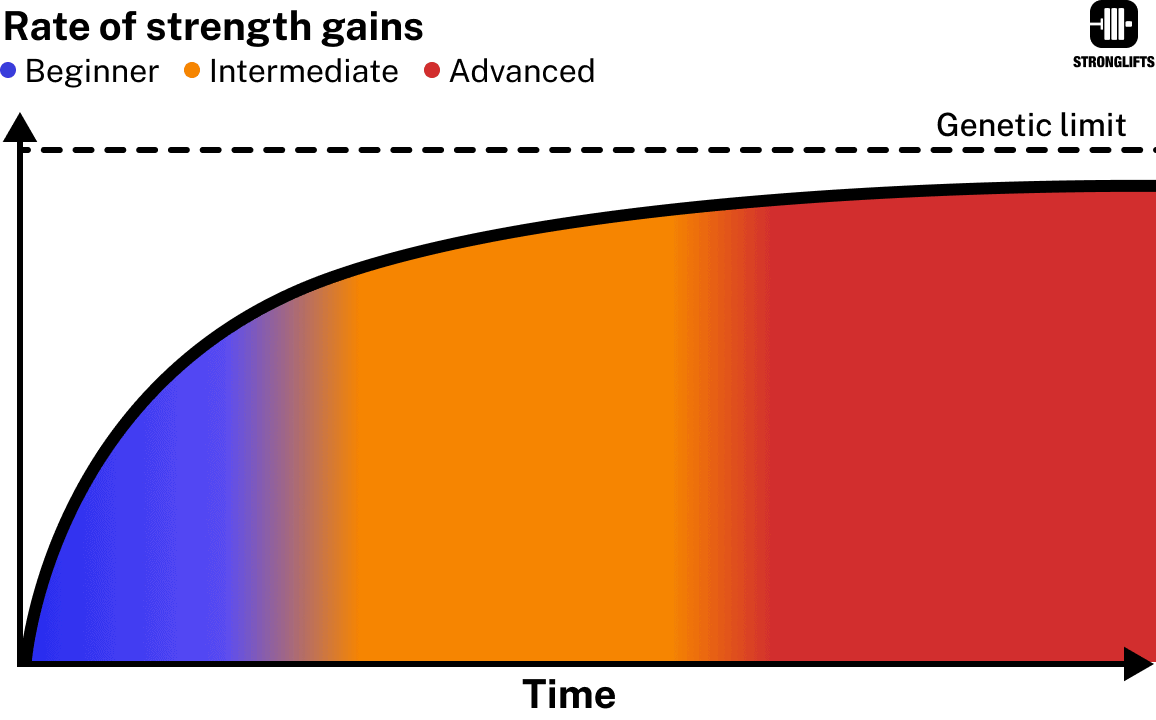

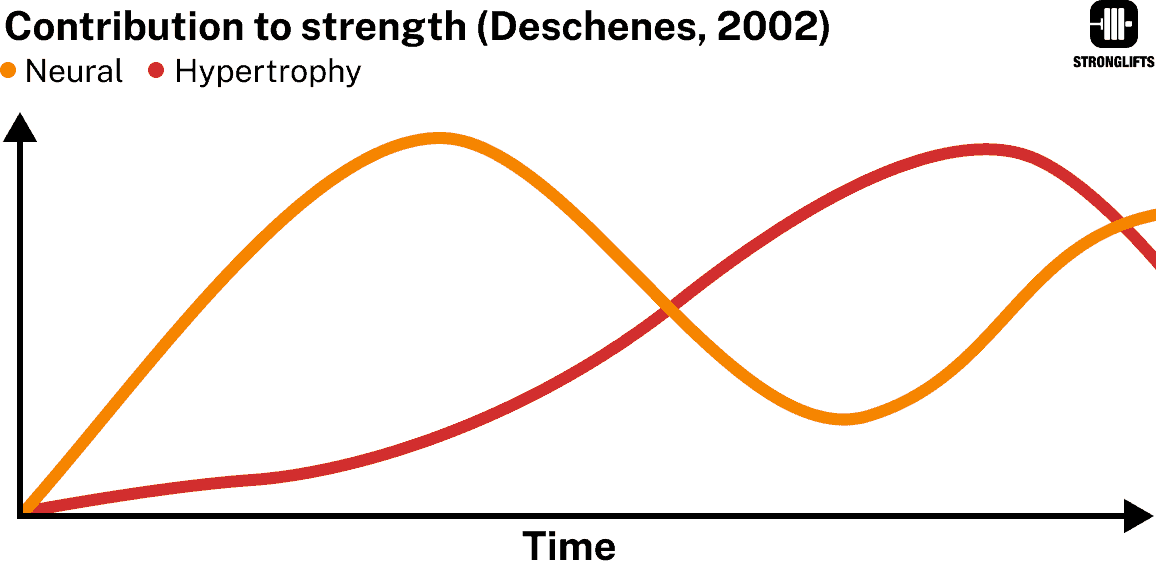

When you start lifting, you can add weight on the bar frequently and easily. The initial strength gains are fast because they’re mostly neural (1). Your body gets better at balancing and lifting the bar using your existing muscles. It’s common for new lifters to double their Squat in a matter of weeks.

These are the easy “beginner gains”, “newbie gains” or “rookie gains”. It’s the gym honeymoon period where you’re hitting personal records every workout. Motivation is high and training is fun because there’s constant progress.

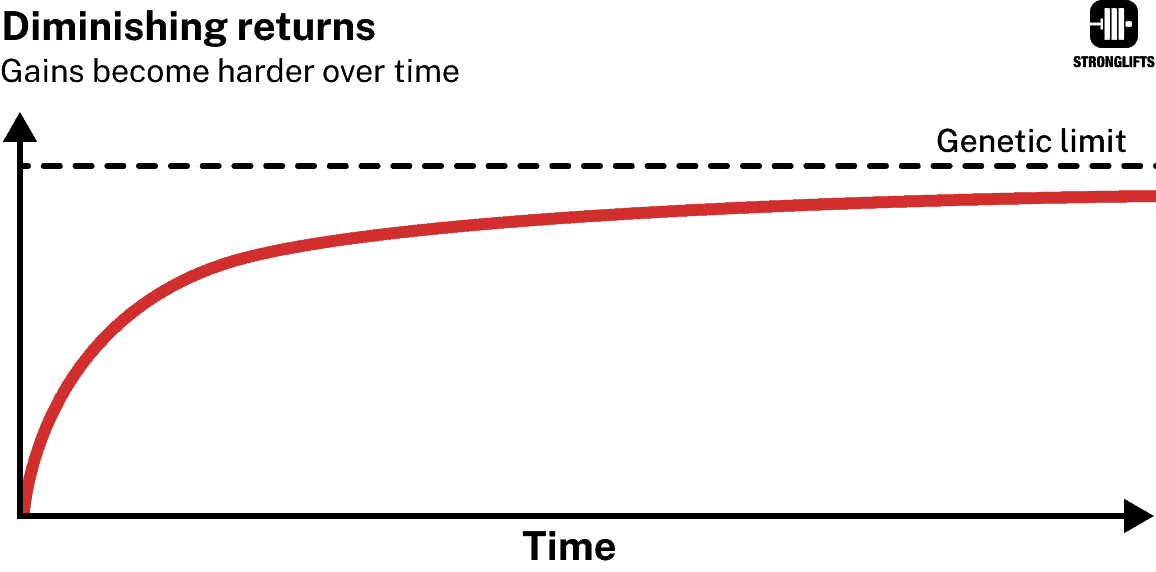

But the easy beginner gains don’t last forever. Strength gains follow the law of diminishing returns (2, 3). Your progress slows down as you get stronger. The average male can easily increase his Squat from 0 to 200lb within 12 weeks. But adding another 200lb to reach 400lb usually takes at least 12 months. It takes many people a few years. Even though you’re adding 200lb in both cases, the second 200lb is harder than the first one.

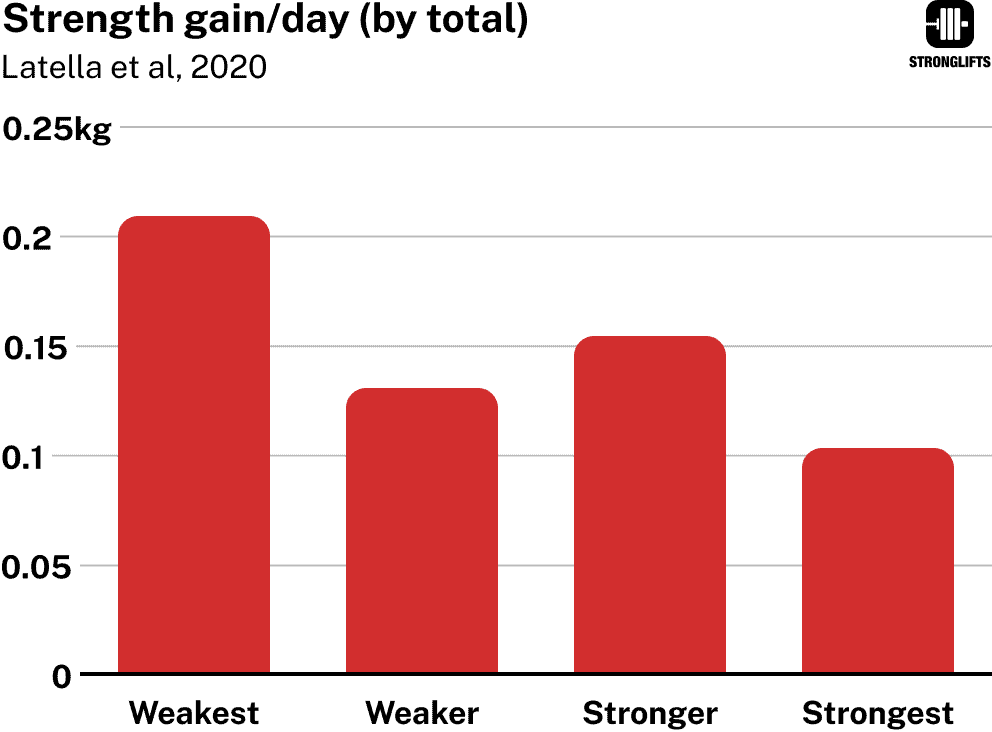

A study by Latella et al looked at the competition results of 1271 male powerlifters from Australia (2). They split them into four groups based on their best total (the sum of your best Squat, Bench and Deadlift). They then looked at how strong they became over time. The average powerlifter was 195lb or 89kg and 27 years old. They did almost 4 competitions over ~2 years.

Here’s how fast they gained strength on their total…

| Latella et al, 2020 | Total before | Total after | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongest | 1245lb | 1336lb | 91lb |

| Stronger | 1173lb | 1279lb | 106lb |

| Weaker | 1120lb | 1219lb | 99lb |

| Weakest | 989lb | 1123lb | 134lb |

| Latella et al, 2020 | Total before | Total after | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongest | 564.5kg | 605.8kg | 41.3kg |

| Stronger | 532.2kg | 580.2kg | 47.9kg |

| Weaker | 507.9kg | 552.9kg | 45.1kg |

| Weakest | 448.6kg | 509.6kg | 60.9kg |

The strongest lifters made less progress than the weakest lifters.

Note that the so-called weakest lifters weren’t actually weak. They had a 989lb total at the start of the study. That’s like a 350lb Squat, 225lb Bench Press and 400lb Deadlift. This may be weak compared to elite lifters, but it’s stronger than your average gym goer. If you lift less weight than this, you should expect to progress at an even faster rate than they did.

In the same study they also calculated the strength gain per day (2). The strongest lifters progressed at half the rate of the weakest lifters.

| Latella et al, 2020 | Strength gain/day (by total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Strongest | 0.225lb | 0.102kg |

| Stronger | 0.355lb | 0.161kg |

| Weaker | 0.302lb | 0.137kg |

| Weakest | 0.465lb | 0.211kg |

The strongest lifters gained 0.102kg strength per day. That’s about 700 grams or 1.5lb per week. This shows that the strongest lifters aren’t adding 5lb on the bar 3x/week. Their training can seem boring to a beginner used to hitting personal records every workout. Not much is going on after all.

And yet stronger lifters can be more happy about adding “only” 5lb on their Bench Press than the typical beginner. A study by Pak et al asked competitive powerlifters and coaches what they considered a “meaningful strength gain” over six weeks of training (4). These were the results…

| Meaningful gains in 6 weeks | Pounds | Kilogram |

|---|---|---|

| Squat | 15lb | 7.1kg |

| Bench Press | 10lb | 4.4kg |

| Deadlift | 18lb | 8.1kg |

| Total | 38lb | 17.5kg |

An extra 10lb to the Bench in six weeks is nothing for a beginner. They can add that in a week. But it’s a big deal for stronger lifters. They understand that the stronger you get, the harder it is to become even stronger. Just lifting the same weight faster and more easily can still count as progress for them.

That’s why it’s good news if your progress has slowed. It means that you’re moving beyond the easy beginner gains. You’re becoming more advanced. You’re becoming stronger. This is what you signed up for.

It’s unrealistic to expect the same fast rate of progress as in the beginning. Unrealistic expectations lead to frustration and disappointment. Some lifters lose motivation and give up once they get stronger. They get discouraged because they can’t add 5lb on the bar as easily as they used to. It’s important to understand that it’s normal for progress to slow down over time.

Slow progress is not a plateau. You’re still making progress. It’s just slower than before. There’s nothing wrong with that. What matters is that you stay focused, patient and dedicated. Nobody becomes really strong overnight. It always takes years of hard work and discipline.

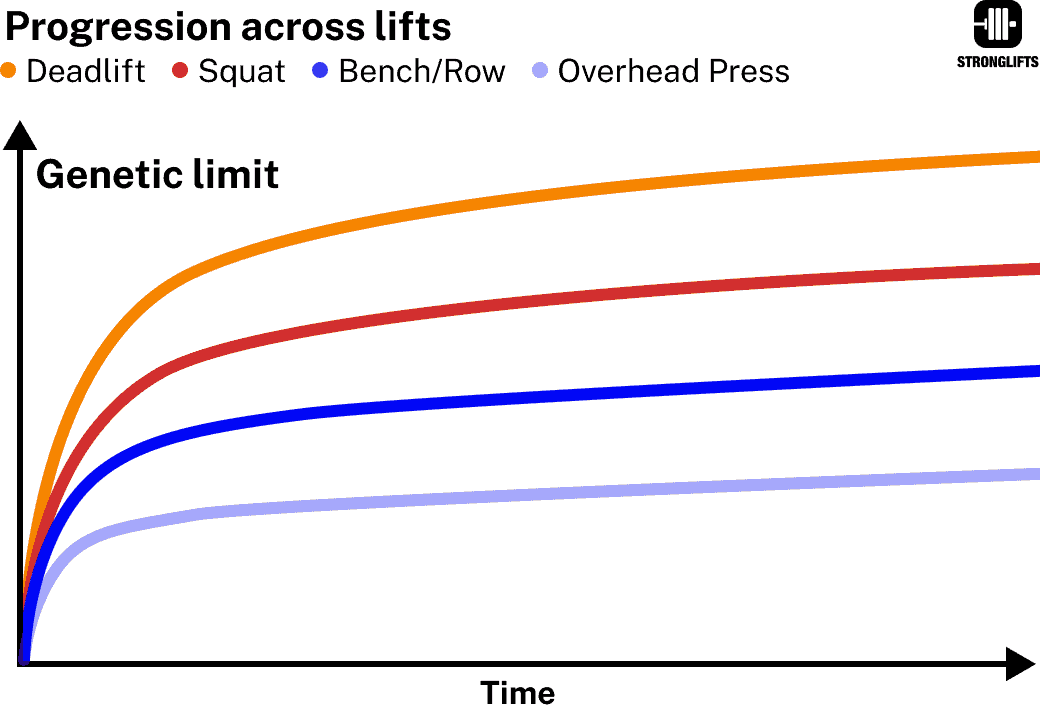

Progress varies across lifts

Different exercises will progress at different rates. You will not lift the same weight on every exercise. You should expect to struggle on some lifts while you’re still making easy progress on other lifts.

Let’s first look at the raw, drug-tested world records in powerlifting for men (5).

| Weight class | 163lb | 183lb | 205lb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deadlift | 723lb | 816.8lb | 823.4lb |

| Squat | 625lb | 706.5lb | 727.5lb |

| Bench Press | 464lb | 475.1lb | 535.7lb |

| Weight class | 74kg | 83kg | 93kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deadlift | 328kg | 370.5kg | 373.5kg |

| Squat | 283.5kg | 320.5kg | 330kg |

| Bench Press | 210.5kg | 215.5kg | 243kg |

Notice how the world records are higher for the Deadlift than the Squat. They’re also higher for the Squat than the Bench Press. This shows you that it’s normal to lift more weight on some exercises than others.

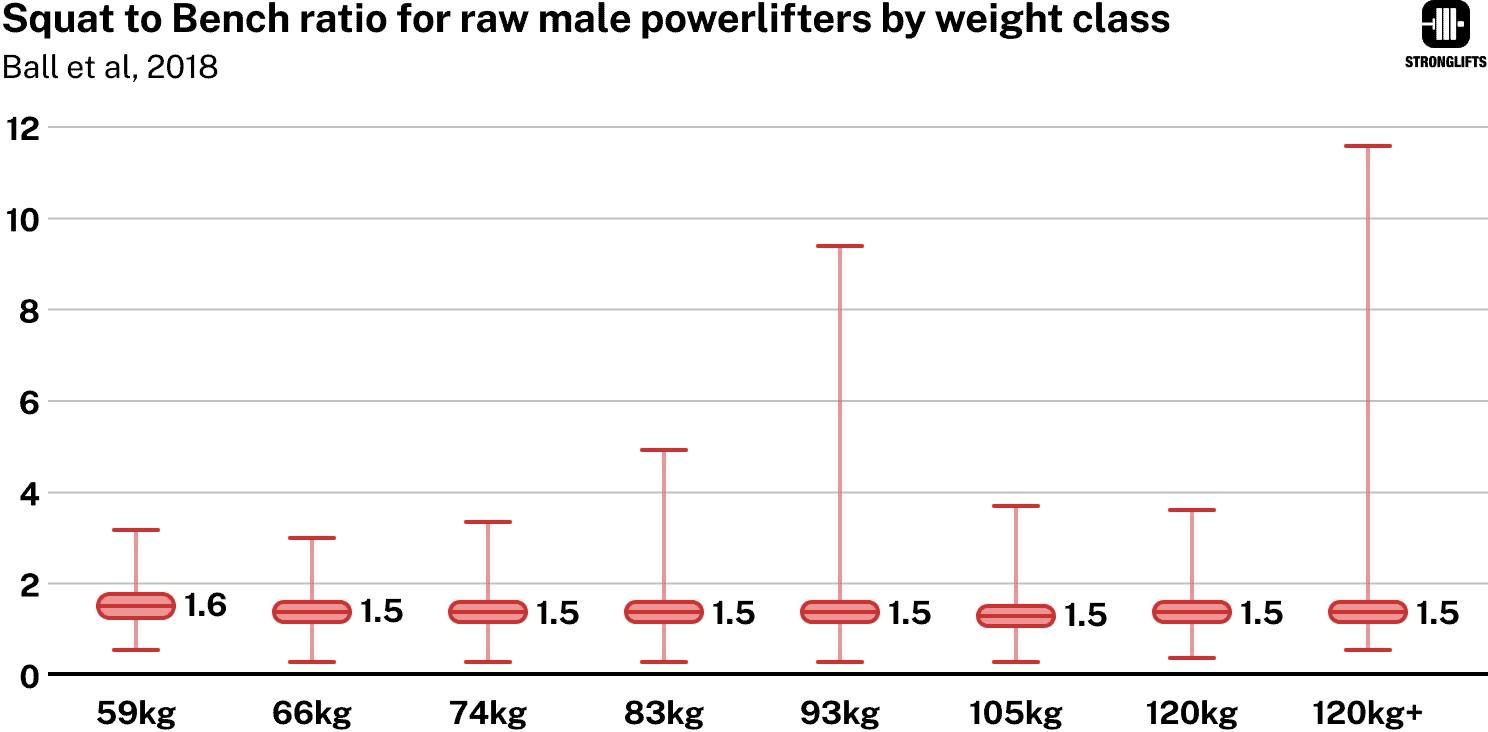

A study by Ball et al analyzed the competition results of 47,913 powerlifters (6). The Squat to Bench Press ratio for men was 1.52. For women it was 1.7. This means that if you’re a guy and Squat about 300lb or 140kg, it would be normal for you to Bench Press about 200lb or 90kg.

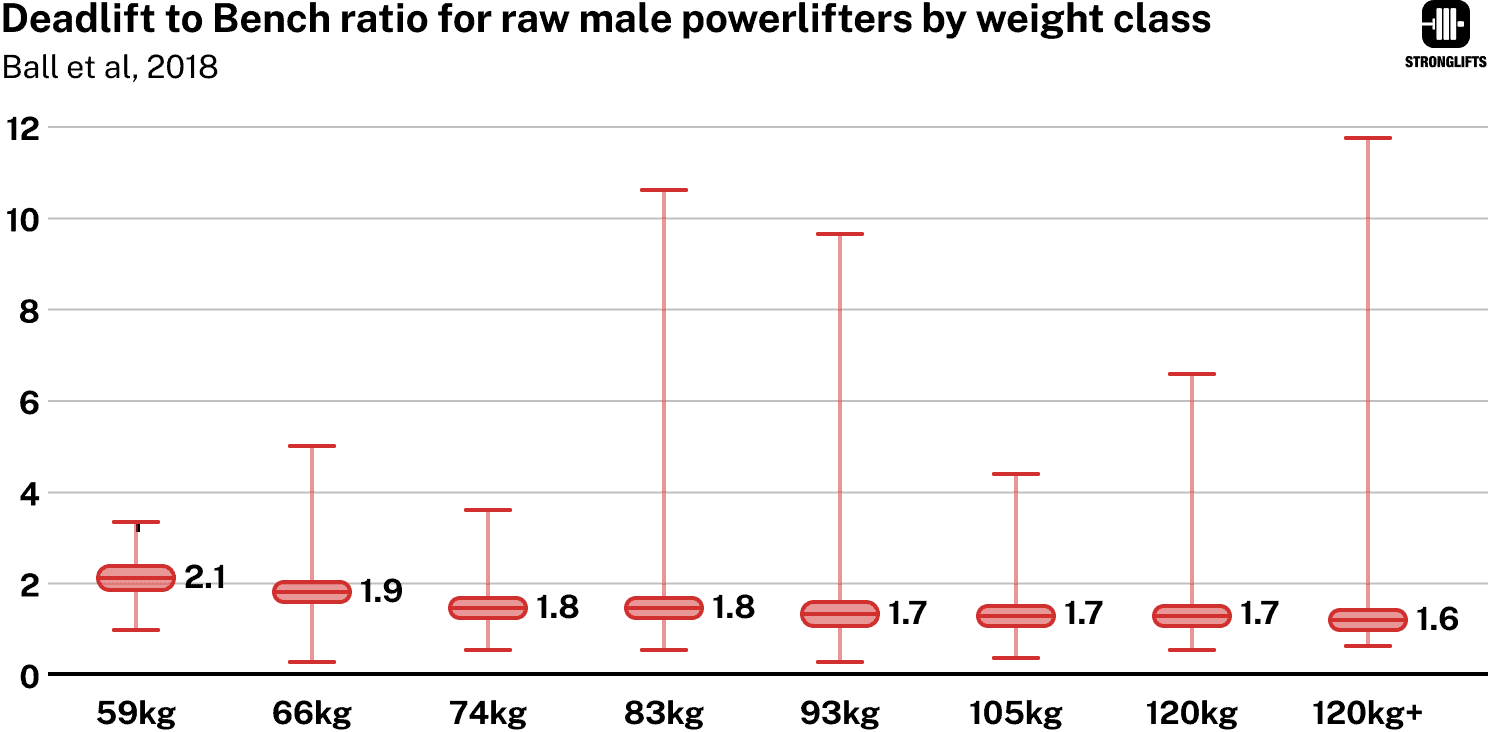

For the Deadlift they found similar results. The average male powerlifter had a Deadlift to Bench Press ratio of 1.75 (6). For women it was 2.19. This means that if you’re a guy who can Bench Press about 200lb or 90kg, you would expect your Deadlift to be around 350lb or 160kg.

It’s common in gyms to see guys Bench Press almost as much as they Squat and Deadlift. They Bench 200lb but only Squat 230lb and Deadlift 275lb. This happens because they focus too much on the upper-body while neglecting their legs. Their Squat and Deadlift are now weak compared to their Bench. Their legs are under-developed and their body imbalanced. They end up with the Johnny Bravo look aka “chicken legs syndrome”.

| Ball et al, 2016 | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Squat to Bench ratio | 1.52 | 1.7 |

| Deadlift to Bench ratio | 1.75 | 2.19 |

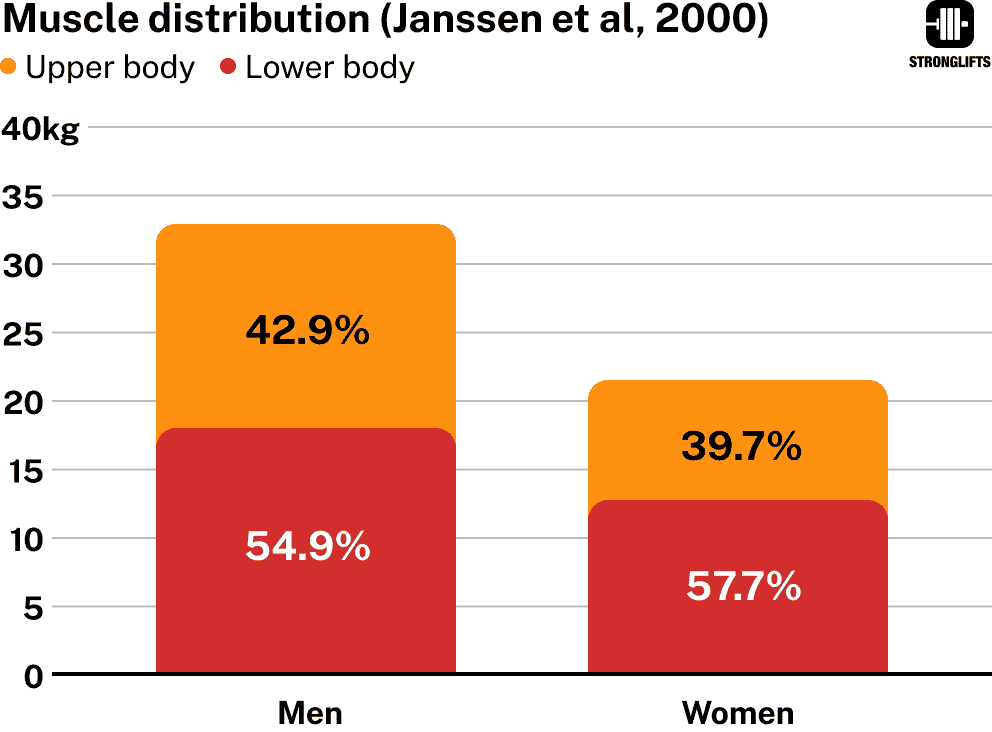

Why do women have a higher Squat/Deadlift to Bench ratio than men? Because they carry a higher proportion of muscle mass in their legs (7). Women carry less muscle in their upper-body and have less muscle mass overall (8). That’s why the Bench Press and Overhead press can be quite hard to progress for them.

How strong should the Overhead Press be? The Overhead Press is not a competitive lift in powerlifting (9). Only the Squat, Bench and Deadlift are. But the Overhead Press was part of Olympic Weightlifting until 1972. Let’s take the old world records and combine them with the powerlifting ones (10, 5). Here’s what we get…

| Weight class | 163lb | 183lb | 205lb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deadlift | 723lb | 816.8lb | 823.4lb |

| Squat | 625lb | 706.5lb | 727.5lb |

| Bench Press | 464lb | 475.1lb | 535.7lb |

| Overhead Press | 367lb | 394lb | 437lb |

| Weight class | 74kg | 83kg | 93kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deadlift | 328kg | 370.5kg | 373.5kg |

| Squat | 283.5kg | 320.5kg | 330kg |

| Bench Press | 210.5kg | 215.5kg | 243kg |

| Overhead Press | 166.5kg | 178.5kg | 198kg |

Note that the weight classes in Olympic weightlifting were 75kg, 82.5kg and 90kg until 1972 (10). In the International Powerlifting Federation they’re 74kg, 83kg and 93kg (5). Not an exact match but close enough.

You can see how the world records are lowest for the Overhead Press, and highest for the Deadlift. Here’s why:

- Deadlifts and Squats work bigger muscles like your legs and back. Bigger muscles can produce more force and lift more weight.

- Deadlifts and Squats work more muscles. They’re not just “for legs”. Your upper-body is involved to hold the bar in your hands or on your upper-back. More muscles working is more weight you can lift.

- Bench and Overhead Press work smaller muscles like your chest, shoulders and triceps. Smaller muscles produce less force. That’s why it’s harder to lift a lot of weight on these exercises.

The result is that your maximum strength potential is lower on the Overhead Press than the Deadlift. Reaching 400lb on Deadlifts isn’t that hard for the average 180lb male. It’s half the world record as you can see above. But Overhead Pressing 400lb would surpass the all time world record. It’s the same weight in both cases, but a lot easier to reach on the Deadlift.

If your maximum strength potential is lower on the Overhead Press than the Deadlift, then using the same increment on both exercises will lead to faster plateaus on the Overhead Press than the Deadlift. That’s why you should use smaller increments on exercises that work smaller muscles.

Here’s an updated table that includes the Bench Press to Overhead Press ratio. I calculated it using ExRx’s strength standards (11). A guy who can bench 200lb or 90kg would typically Overhead Press about 125lb or 57kg. Sounds about right in my lifting and coaching experience.

| Strength ratio | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Deadlift to Bench Press | 1.75 | 2.19 |

| Squat to Bench Press | 1.52 | 1.7 |

| Bench to Overhead Press | 1.6 | 1.4 |

The bottom line is that different exercises will progress at different rates. And so it’s normal to struggle on the Overhead Press or Bench Press while still making easy progress on the Squat and Deadlift.

Don’t make the mistake of holding back the weight on your Squat or Deadlift until your Overhead Press catches up. It will never catch up because you will not lift the same weight on every exercise. If you hold back on your Squat and Deadlift, you’ll simply undertrain those lifts.

Common plateau mistakes

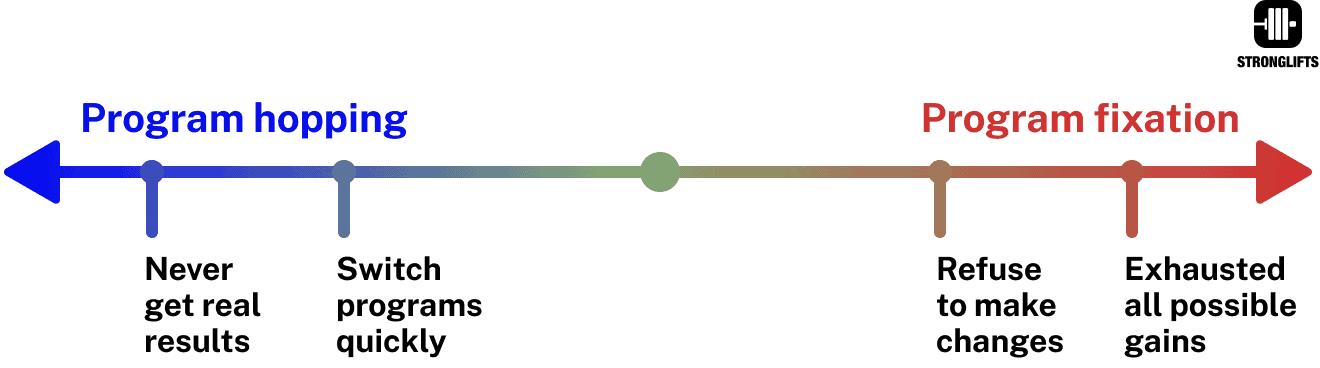

Program hopping

When beginners hit a plateau, they often look for a new and “better” program. They’re quick to hop from one training program to the next one. What they don’t realize is that the program is only one part of the puzzle (12).

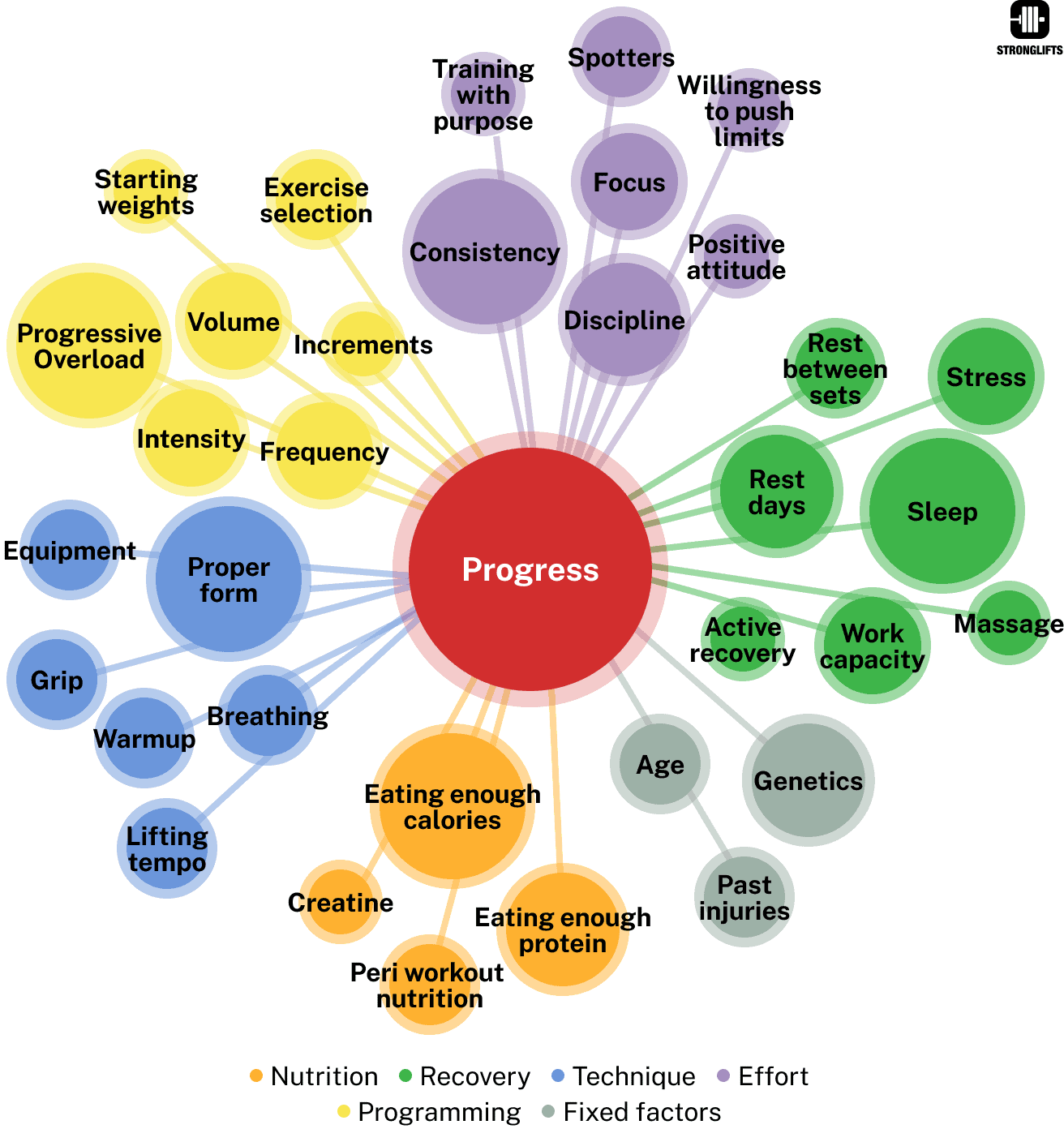

Many factors determine your ability to add weight on the bar, get stronger and build muscle. This includes: protein intake (13), calorie intake (14), sleep (15), recovery (16, 17), stress (18), work capacity, rest periods (19, 20), technique, lifting tempo (21, 22), breathing, warmup, grip (23, 24), equipment, discipline, consistency, mental focus (25), effort (26, 27), positive attitude, spotters (28), starting weights, increments (29), etc.

You can make your existing program better by optimizing all the factors that influence your ability to progress.

Example: a skinny guy emails me complaining about plateaus. But he’s only 120lb at 5’8″ (55kg at 1m73). This is like a 300lb / 140kg person complaining that their sprint time isn’t improving. You need to get your body to the right size for the job. The fastest sprinters aren’t 300lb. And the strongest 5’8″ lifters aren’t 120lb. They’re a lot bigger than that.

A study by Keogh et al found that the stronger powerlifters were bigger than the weaker ones (30). Strength = skills × muscle (31, 32). Bigger muscles can produce more force. They can lift heavier weights.

| Keogh et al, 2009 | Stronger powerlifters | Weaker powerlifters |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 5’6″ | 5’7″ |

| Weight | 209lb | 196lb |

| Body-fat | 16% | 15% |

| Squat | 573lb | 402lb |

| Bench | 373lb | 250lb |

| Deadlift | 568lb | 459lb |

| Keogh et al, 2009 | Stronger powerlifters | Weaker powerlifters |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 170cm | 174cm |

| Weight | 95kg | 89kg |

| Body-fat | 16% | 15% |

| Squat | 260kg | 182kg |

| Bench | 169kg | 113kg |

| Deadlift | 258kg | 208kg |

The average powerlifter in this study was ~5’7″ and +185lb (1m73 and 84kg). Other studies of powerlifters and even bodybuilders found similar results (33, 34). I’m 5’8 and 185lb which even makes me “underweight” for powerlifting. If you’re 5’8 and 120lb, you can switch programs as much as you want. You’ll always struggle to progress because your body isn’t the right size for the job. Lifting alone won’t make you bulk up. You need to eat more for that.

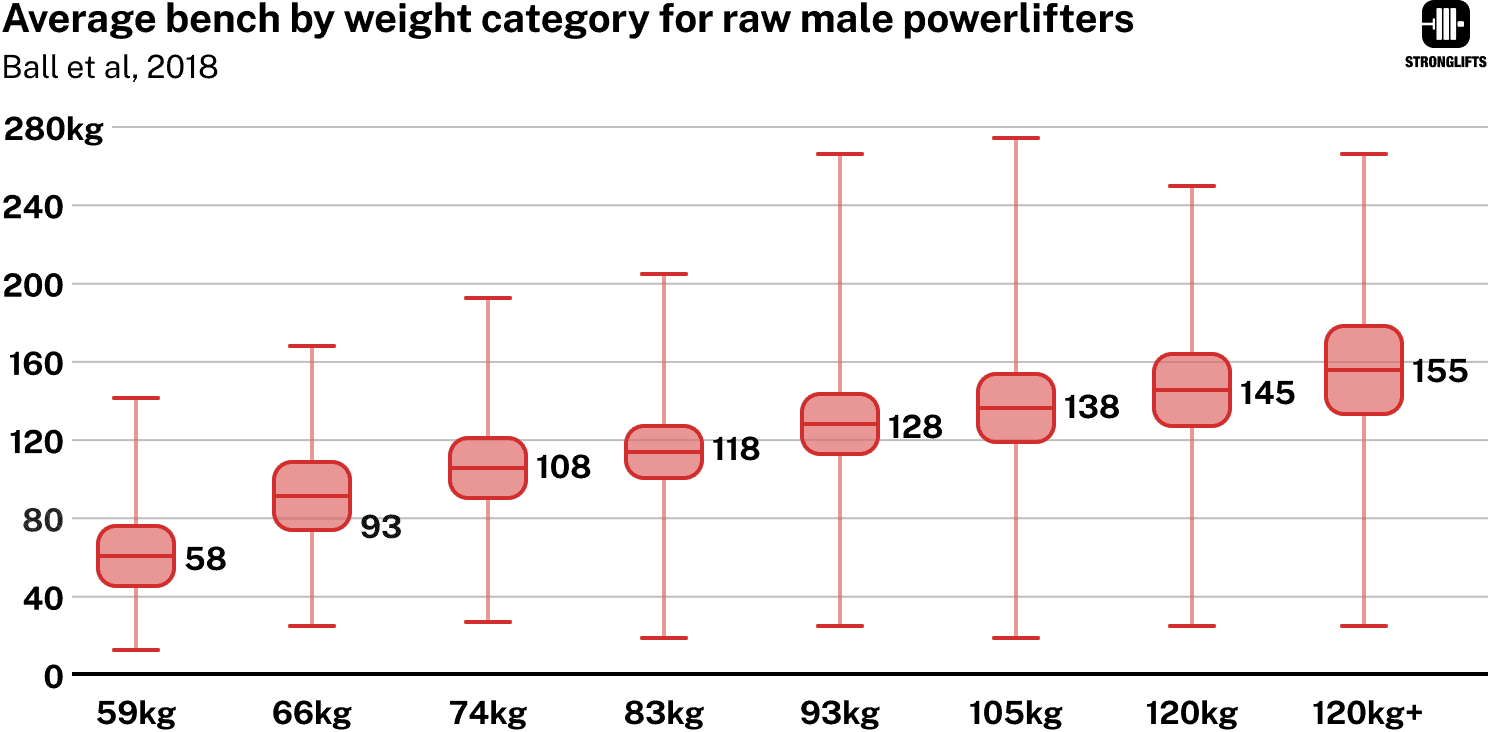

The study by Ball et al showed that the heavier the powerlifter was, the more weight they could lift (6). That’s why strength sports have weight classes – it levels the playing field by grouping lifters of similar weight together. The biggest powerlifters would win everything otherwise.

The average 83kg male powerlifter has a Bench Press of 118kg vs 93kg for 66kg lifters. That’s a difference of 25kg or 55lb. This shows the importance of body weight when it comes to lifting heavy. Note that these are weights done for one rep. They’re about 20% higher than what you’d lift for 5×5.

| Weight class | Avg Bench Press | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 58kg / 128lb | 58kg / 128lb | |

| 66kg / 146lb | 93kg/ 205lb | +35kg / 77lb |

| 74kg / 163lb | 108kg / 238lb | +15kg / 33lb |

| 83kg / 183lb | 118kg / 260lb | +10kg / 22lb |

| 93kg / 205lb | 128kg / 282lb | +10kg / 22lb |

| 105kg / 231lb | 138kg / 304lb | +10kg / 22lb |

| 120kg / 265lb | 145kg / 320lb | +8kg / 15lb |

| 120kg+ / 265lb+ | 155kg / 342lb | +10kg / 22lb |

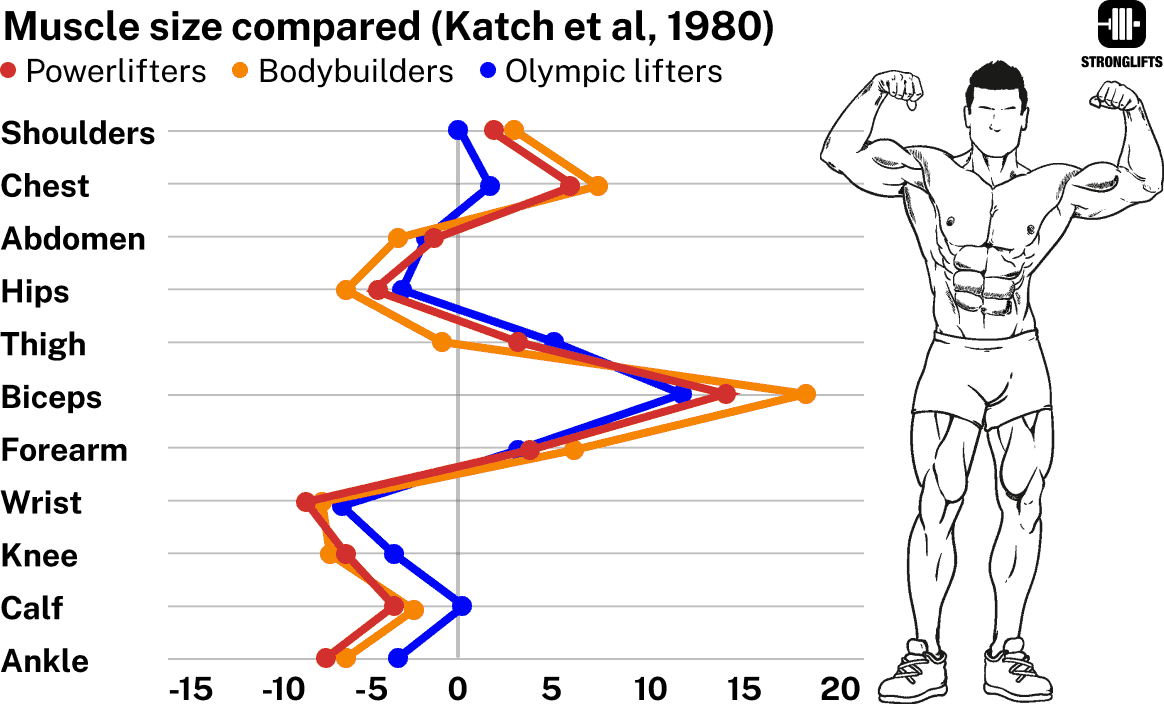

Many people don’t realize that strength = skills × MUSCLE (30, 31, 32). They think powerlifting only builds strength. It’s “all about CNS”. Building muscle supposedly doesn’t matter for lifting heavy weights. And yet a study by Katch et al found that powerlifters have 97% of the muscle mass of bodybuilders (33). Anyone who has gone to a powerlifting competition can attest this: the strongest lifters are almost always the more muscular ones. They’re so muscular the average person often confuses them for bodybuilders.

Building muscle is a slow process. It requires adding tissue. Just think how long it takes to grow longer hair or nails. Most of your initial strength gains are therefore neural (1). Your body gets better at lifting the bar using your existing muscles. This process happens faster because it comes down to optimizing what you already have. After a while you know how to Squat. There’s always room for improvement but you’ve acquired most of the skills. And so you should expect diminishing returns from improving your technique more.

Further strength gains require you to increase your muscle mass (35). Your muscles have to get bigger to lift heavier weights. Because again, strength = skills × MUSCLE. You can’t rely only on neural gains and technique to get stronger. That’s playing half the field. It’s ineffective.

Skinny guys who are 5’8″ and 120lb plateau because they don’t eat enough calories and protein to support muscle growth (13). Their muscle mass can’t increase and so the weight on the bar can’t go up. Many people waste years hopping from program to program while neglecting their diet. That’s why they don’t progress. When told to eat more, the usual counter is that they don’t want to get fat. But you can avoid that by eating lots of protein (36). NOTE: if you have +25% body fat with excess weight you shouldn’t eat more calories. You should eat less. Eat more is for skinny, underweight lifters only.

This example illustrates how your training program is only one part of the puzzle. Nutrition, recovery, technique and effort are other crucial parts that affect your progress. If you neglect them, then it doesn’t matter which program you follow. None will ever work well.

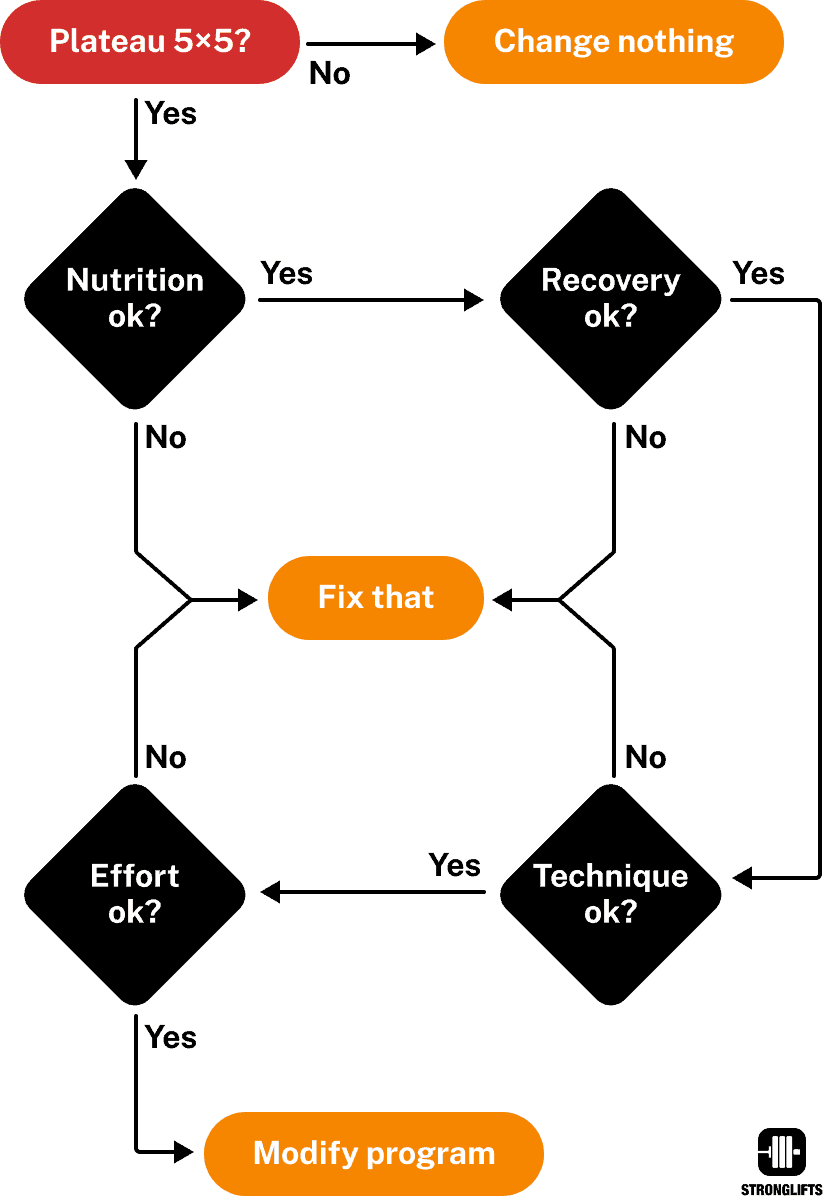

Plateaus are a wake up call to look at all the factors influencing your progress. Failing reps can happen for many, many reasons. Changing programs is easy but it can lead to missed opportunities to improve your nutrition, recovery, form, etc. Any program will work better if you work on that. There’s a huge potential for quick gains and breaking plateaus if you improve all the factors that influence your progress instead of simply changing programs.

Read: what to do if you fail reps on Stronglifts 5×5.

Program fixation

On the other end of the spectrum you have lifters who do Stronglifts 5×5 for too long. They’ve built a lot of strength and muscle but have now hit a plateau. They’ve exhausted all the gains but refuse to make a change. Instead of program hopping, they suffer from “program fixation” (this is not a medical condition or disease but rather a made-up term for contrast).

Over the years, I’ve had many conversations with Stronglifters who were stuck but unwilling to switch things up. Here are the three most common reasons people have given me for this resistance to make a change…

- They’ve become attached to the program. They’ve done Stronglifts 5×5 for several months. They’ve become consistent, stronger, more muscular, leaner and fitter. They’ve achieved better results in a short amount of time than they ever thought was possible. They’ve invested a lot of time and effort into the program. They finally feel in control. They don’t want to give all of that up by switching to something new and unfamiliar. They don’t want to risk losing progress.

- They’re too busy right now. They don’t want to spend time and energy learning new workouts and exercises. They have a simple routine that keeps them fit and consistent. They don’t want to disrupt that by switching to something new. Their lack of progress bothers them but not enough to switch things up right now.

- They want to reach a certain weight first. They want to Squat 300lb / 140kg or so before they stop Stronglifts 5×5. What they don’t realize is that the same gains can be achieved if they switch things up, probably even more easily. Yet they force themselves to push harder and harder. This isn’t the best idea as it can result in overuse injuries.

Some people think I’ve been doing Stronglifts 5×5 for the past 27 years. Not the case. The principles of doing mostly compounds and applying progressive overload have always been central to my training. But the basic Stronglifts 5×5 workouts A/B were never meant to be done your whole life. You were always supposed to move on once you became stronger.

There’s only one situation where you can do Stronglifts 5×5 forever. You lift for say three months, quit for nine months, and then resume. If you train like this, then you can do Stronglifts 5×5 forever to regain lost strength and muscle mass year after year. Some people do this and it works. But I’ve never done this “yo-yo lifting”, and don’t recommend it. You should be consistent.

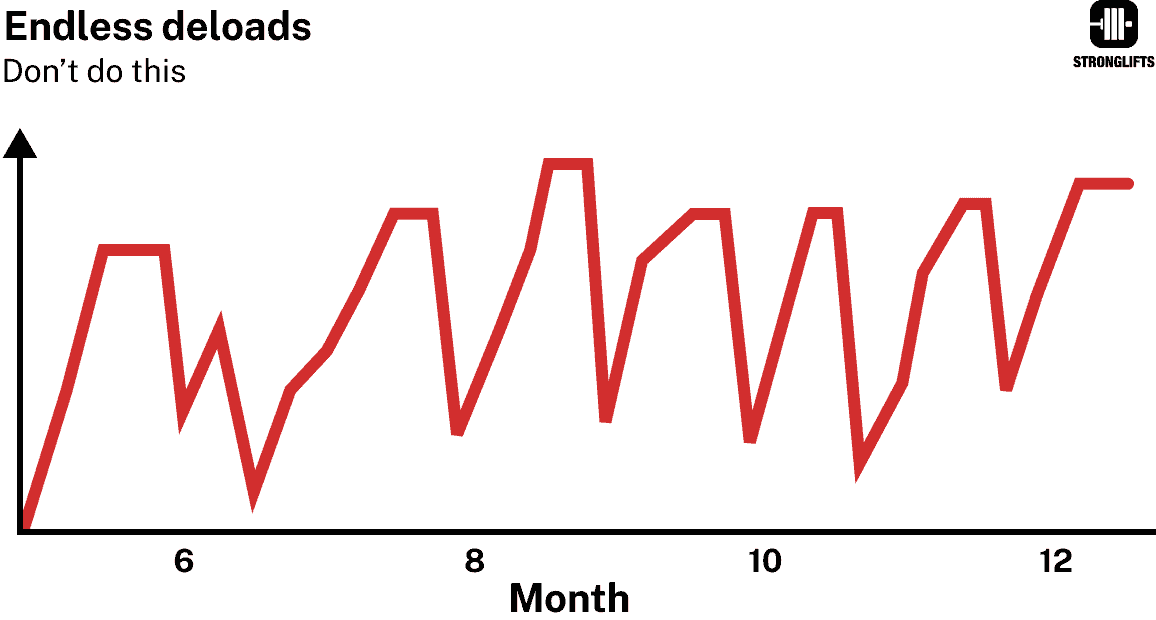

Endless deloads

People who do Stronglifts 5×5 for too long often try to break through plateaus by doing endless deloads. They think a deload is some sort of magic fix that will suddenly add 50lb to their Squat. This idea is appealing because it sounds simple and easy. But it’s unfortunately now how this works.

Deloads don’t make you stronger. They make you rest.

That rest can help you lift more weight. That’s why powerlifters deload before competitions (37, 38). Deloads or “tapers” clear fatigue that accumulated during the past training weeks. They help them achieve full recovery. This maximizes performance (39). It helps them lift more weight than they didn’t deload. But the deload isn’t what builds all the strength. It simply helps them better display the strength they’ve built during the past training weeks.

Think of it like studying for an exam. It’s good to take regular breaks to allow your mind to rest and recharge. Those breaks can help you study with more focus afterwards. However, breaks aren’t the primary factor in passing your exams. It’s your actual time spent studying that determines that.

Same with deloads. It’s fine to do a lighter week or two if you feel tired. That will clear fatigue. But it’s not the primary driver of strength. Training is. If the training is no longer sufficient to drive progress because your body is stronger and more muscular than before, then the training needs to be adjusted.

What causes plateaus?

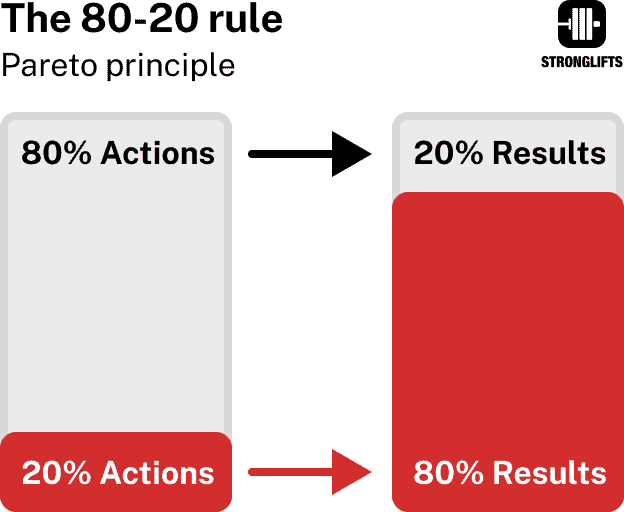

Skipping the basics

As explained above, multiple factors influence your ability to progress. One major reason for plateaus is therefore to skip the basics. Pareto’s principle states that 80% of your results will come from 20% of your actions. That 20% are basics like proper nutrition, recovery, technique, effort, etc.

Many people look for complex solutions when they plateau. They’ve been told that building strength and muscle is complicated. And so they end up wasting lots of time, effort and sometimes money on irrelevant details. The truth is that the fundamental principles of strength and muscle building are quite simple. The process is similar to gardening: if you want a plant to grow, you need to create the right conditions for that growth to happen.

Many lifters don’t have the fundamentals down. They skip the basics and focus on minor details. Growth can’t happen because the right conditions haven’t been set. Common mistakes include…

- Poor nutrition – low calorie intake, low protein intake, etc

- Poor technique – incorrect grip, stance, breathing, poor equipment, etc

- Poor recovery – lack of sleep, lack of rest between sets/workouts, etc

- Poor effort – inconsistency, lack of focus, lack of spotters, etc

Skipping the basics will result in plateaus. You’ll fail reps more and struggle to add weight. Step one is therefore to make sure that you’re not making fundamental mistakes. Read what to do if you fail on Stronglifts 5×5.

The rest of this guide assumes that you have the fundamentals down already but are still unable to progress. I will show why Stronglifts 5×5 can’t work forever, and what program modifications are needed to break plateaus and start hitting personal records again.

Unsustainable progression

You can’t add 5lb on the bar 2-3x/week forever.

When you start Stronglifts 5×5, you can easily add 5lb to your Squat 3x/week. But once you’re stronger, once you’re lifting heavier weights, then adding the same 5lb on the bar becomes harder. Eventually each workout can turn into a physical and mental battle. You start to dread the workouts, fail reps all the time, and feel a constant need for deloads.

As discussed above, strength gains follow the law of diminishing returns (2, 3). When you start lifting, the weight goes up quickly. These are the easy “beginner gains”. But the stronger you become, the harder it is to get even stronger. Stronger lifters get stronger at a slower rate than weaker lifters. The math is clear: 5lb on the 45lb bar, 3x/week, for 52 weeks is 825lb or 374kg. Few people can lift that. And so this rate of progress is unsustainable.

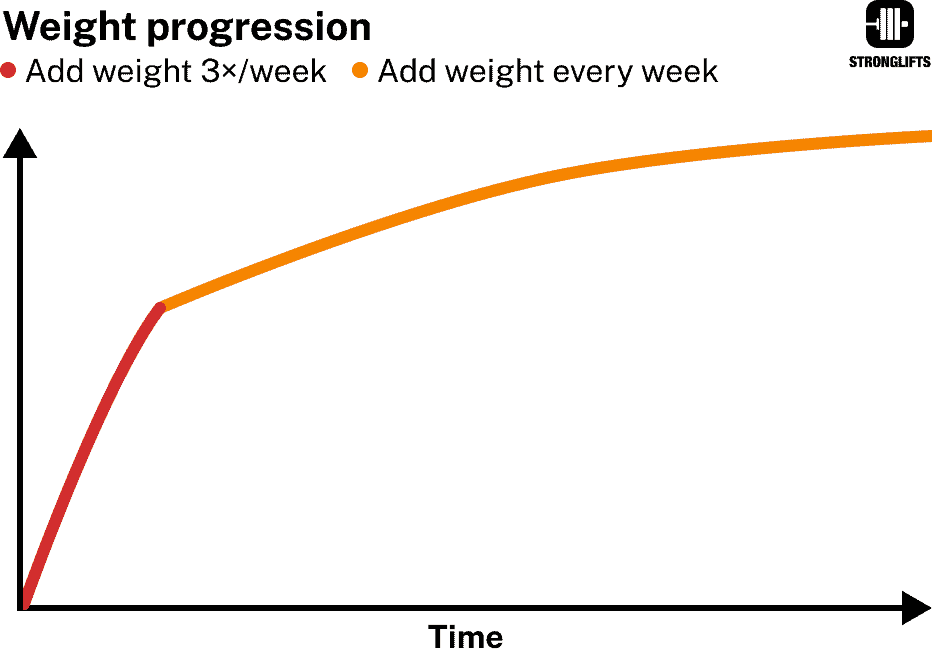

If progress slows down for all of us as we get stronger, then the obvious fix is to switch to a slower rate of progression. Use one that your body can handle – not one you wish for. You can’t force your body to get stronger faster by throwing more weight at it. It will get stronger at the rate that it can get stronger. If adding weight 3x/week has become too much for your body to handle, then stop doing that. Start adding weight once a week instead.

Notice how transitioning to a slower weight progression aligns with the law of diminishing returns. Progress is steeper and faster at first (“beginner gains”). But it slows down as you get stronger (diminishing returns).

The million dollar question is “when should you make this switch?” Impossible to say because there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Your progress is influenced by too many factors. Look at your progress and listen to your body. If you think you’d do better with a slower progression, then make the switch. Simple.

You can set the Stronglifts app to add weight less frequently. Open the app – tap start workout – tap the weight – scroll down to progression – change the increment frequency from every workout to every 3, 4, or 5 workouts.

But there’s one big problem with doing that.

Lifting the same weight for several workouts can be boring. You can feel like you’re not making progress because you don’t see the weight on the bar increase. There’s an easy solution to that. I’ll show you below.

Too many Squats

Doing the same Squat 3x/week, for five straight sets of five, with increasingly heavier weights in each workout, becomes too much after a while.

Squatting 3x/week serves an important purpose when you start Stronglifts 5×5. One big priority of the program is to help you learn proper form on the Squat, Bench, Deadlift, Overhead Press and Barbell Row. Good technique helps you engage more muscles. It helps you lift the weight more efficiently and easily. It helps you complete more reps and lift more weight. It helps you progress better. It decreases the risk of getting hurt.

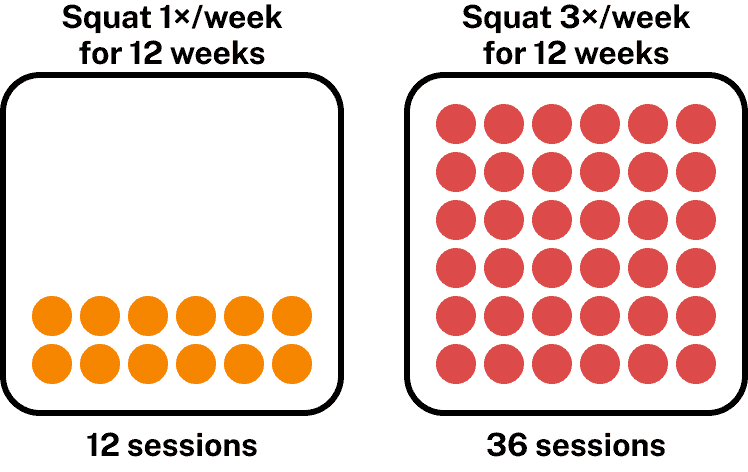

The more you practice an exercise, the faster your form improves. If you do the lift more often, you get more practice.

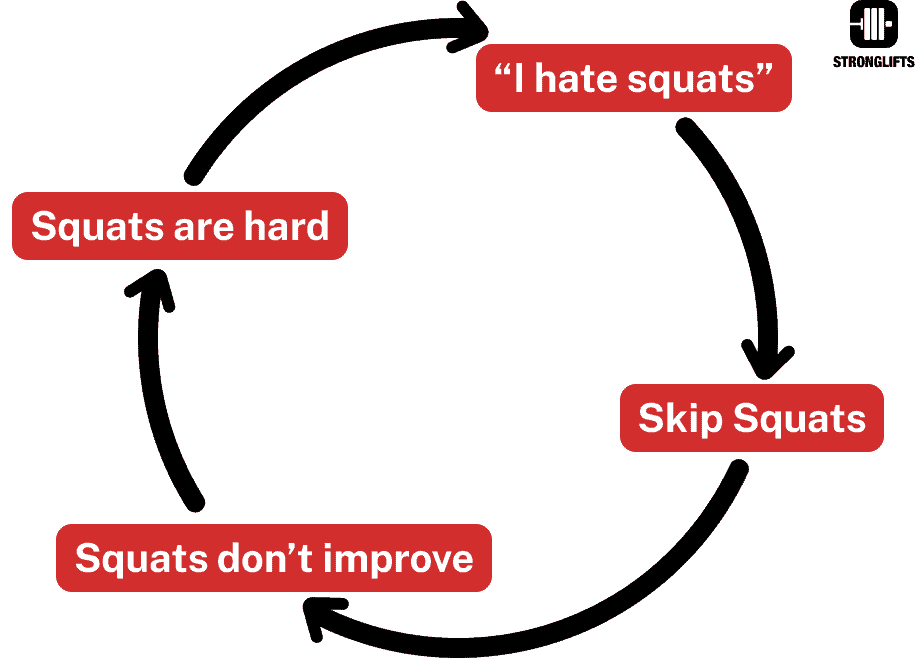

The Squat is a particularly difficult exercise to learn. The bar moves a greater distance than on other lifts. You’re using bigger and more muscles than on the presses and rows. You’re lifting a heavier weight. That weight rests on your upper-back where you can’t see it. It presses you down which is intimidating. You have to Squat all the way down and come back up. You can get stuck under the weight if you fail. Squats are hard, scary, and that’s why many people skip them. This results in poor form from a lack of practice.

This is the reason we Squat 3x/week on Stronglifts 5×5. If you Squat 1x/week you get 12x practice over 12 weeks. In contrast, if you Squat 3x/week, you get 36x practice. That’s 24x more opportunities to improve your Squat form. You could skip one workout a week because of reasons and still get double the practice than someone Squatting only 1x/week.

Squats work a lot of muscles. They work big muscles like your legs and back. Bigger muscles can produce more force. Squatting 3x/week helps you acquire basic technical skills faster. You stop being scared of Squats because you do it so often. All of that helps you progress better. It explains why you can easily add weight every workout for so long on Stronglifts 5×5.

But the math is clear: adding 5lb on the bar 3x/week leads to 780lb or ~355kg in a year. That’s more than the world record for males of average weight. Most of us will never be able to lift that much weight. And so even though doing the same Squat 3x/week for 5×5 works great at first, the rate of progression is unsustainable. It has to slow down over time.

The obvious solution would be to start Squatting 1x/week. That would slow down the progression. 5lb/week = 260lb or 118kg/year. If you microload and add 2.5lb/week, you get 130lb or ~60kg/year. Much more realistic.

The problem is that Squatting 1x/week would give us little technical practice. Strength = skills × muscle (31, 40), remember? We still need frequent Squat practice to continue to improve our skills and get stronger. And so we need a better way to slow the progression. We’ll discuss this further below.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate has a lower Squat frequency. Check it out.

Lack of variety

You cannot expect infinite strength gains by repeatedly doing the exact same workouts for months and years on.

Many lifters dream of finding a simple program they can do for the rest of their lives without ever making changes. “Set and forget”. I’ve searched for that program too. It doesn’t exist. No matter how good the program may be, your body will adapt to it. The same workouts that were once super effective will become less effective over time because your body got used to them. The need for variety is a fundamental principle of progression (41, 42).

You’re not the same person you were when you started Stronglifts 5×5. You’re stronger and more muscular. You’re technically more proficient. You have more work capacity. You’re fitter and can handle more work.

Your body has changed.

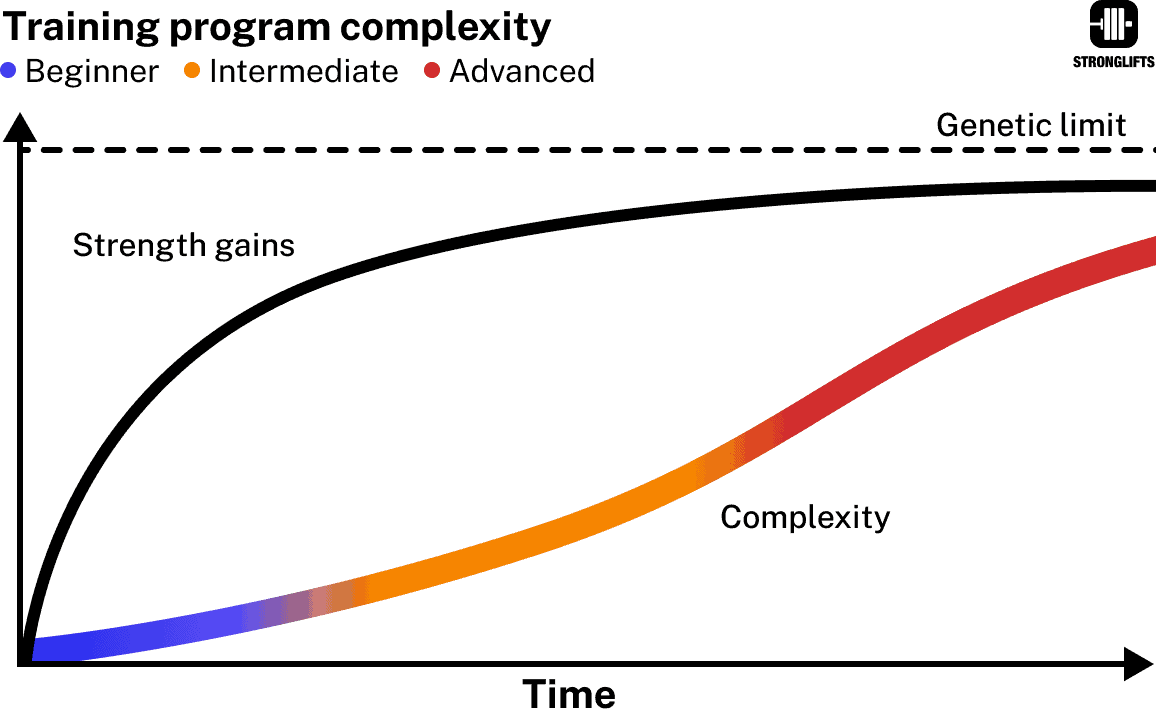

The same workouts that were once challenging may no longer be challenging you enough to stimulate further progress. The same workouts that increase your Squat from 0 to 200lb won’t necessarily increase it to 400lb too. If getting stronger was that easy then everyone in the gym would be doing the same workouts forever. We know that’s not the case. You need variety as you get stronger. And so your training will become more complex over time.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate introduces exercise variety. Check it out.

Lack of volume

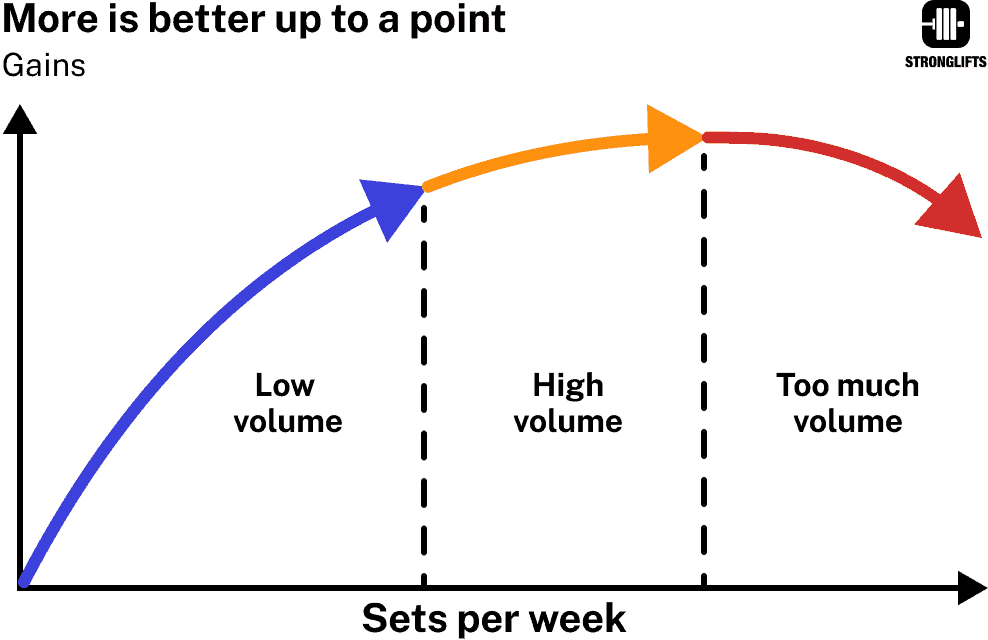

If you’re not making progress, then you may simply not be doing enough.

Progressive overload is one of the fundamental principles of progression (41). You must try to lift more weight over time to increase your strength. However doing just one heavy rep per week would be too little work. You also have to make sure you do enough weekly sets. That’s your volume.

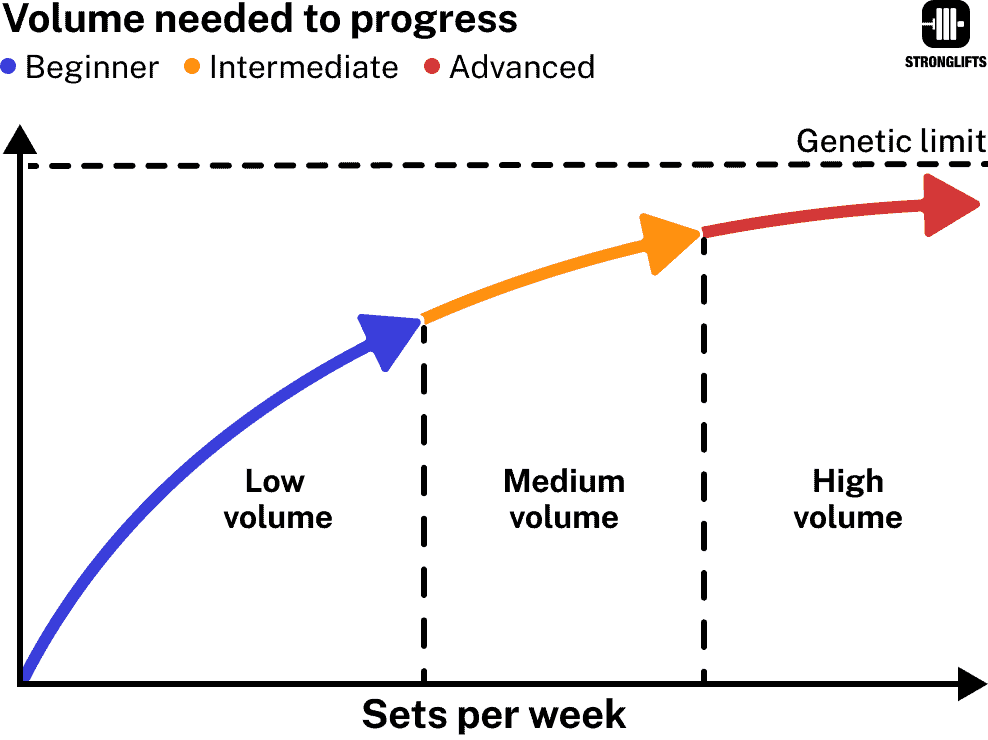

The amount of volume you need to make progress increases over time. New lifters usually need more volume to grow stronger and bigger legs. Their upper body can build strength and muscle fine with less volume at first. But over time, the volume needs to increase for the upper body too.

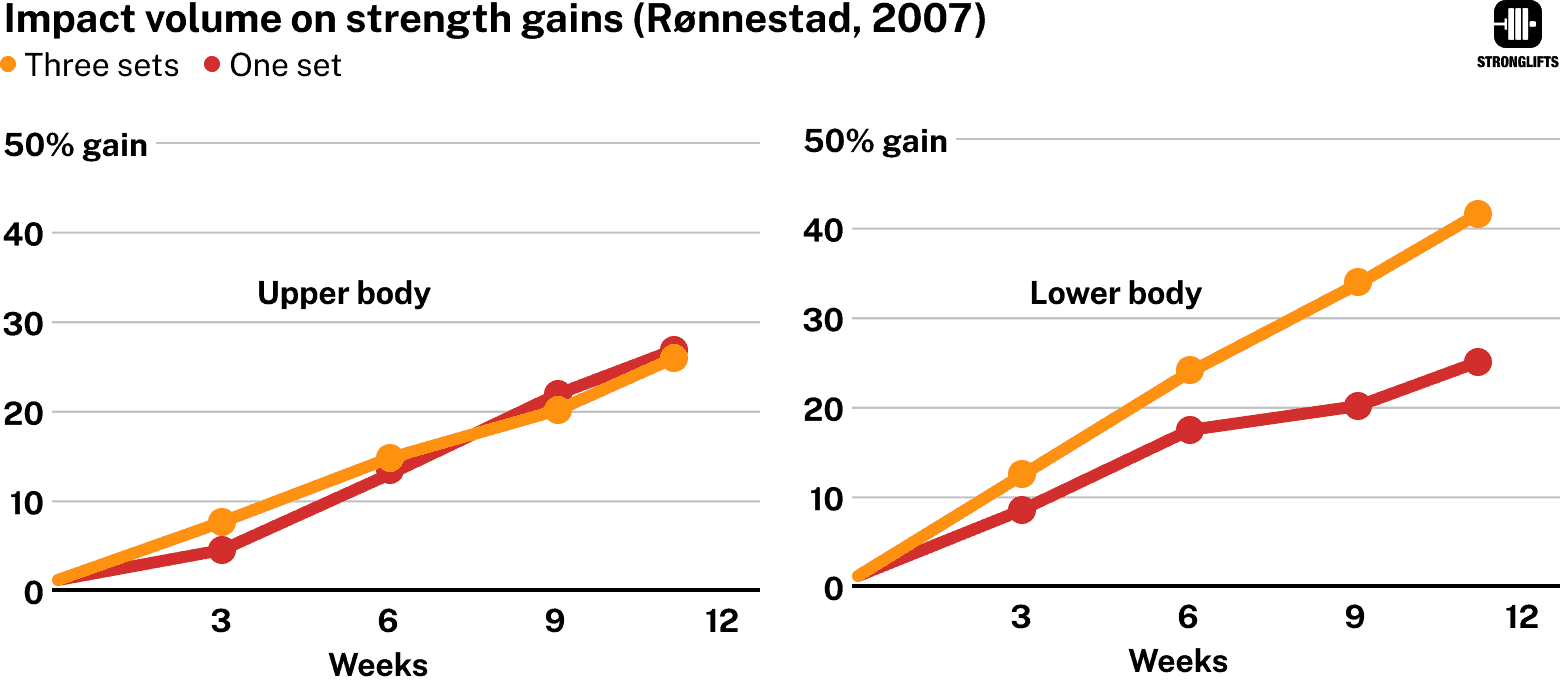

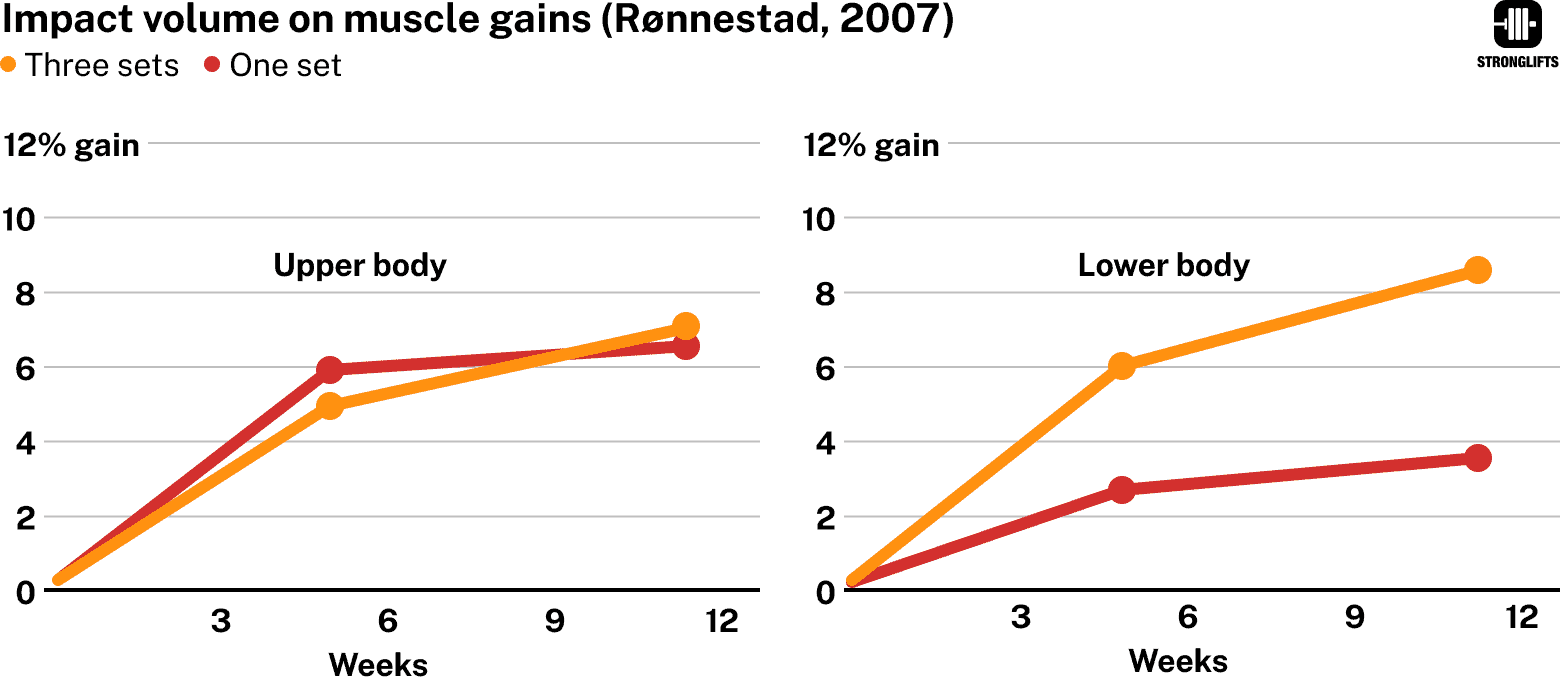

A study by Rønnestad et al compared one vs three sets for building strength and muscle (43). Untrained men lifted weights 3x/week. They did leg press, leg curls, leg extensions, chest press, rows, lat pulldowns, curls and shoulder press. One group did only one set per exercise. The other group did three sets per exercise. Here’s how much strength they gained…

The group that did three sets per exercise built stronger legs than the one that only did one set. However, both groups gained the same amount of strength in the upper body. Three sets were better for legs only.

When they looked at muscle gains, they found similar results. Three sets built bigger legs. But it was again no better than one set for the upper body.

You use your legs more in daily activities. And so your legs are more trained when you start lifting (44). That’s why they need more volume than your upper body to build strength and muscle.

Think about it: every day you sit on chairs, sofas and toilets and squat back up. You bend through your legs to pick things up. You climb stairs, ride bikes, run and walk. All of that works your legs. But how many times do you push or pull something away using your upper body? You mostly grip things. And so your upper body is less trained when you start lifting. It responds to less volume than your legs. That’s one more reason Stronglifts 5×5 starts with 3x/week Squats – to avoid chicken legs aka the Johnny Bravo look.

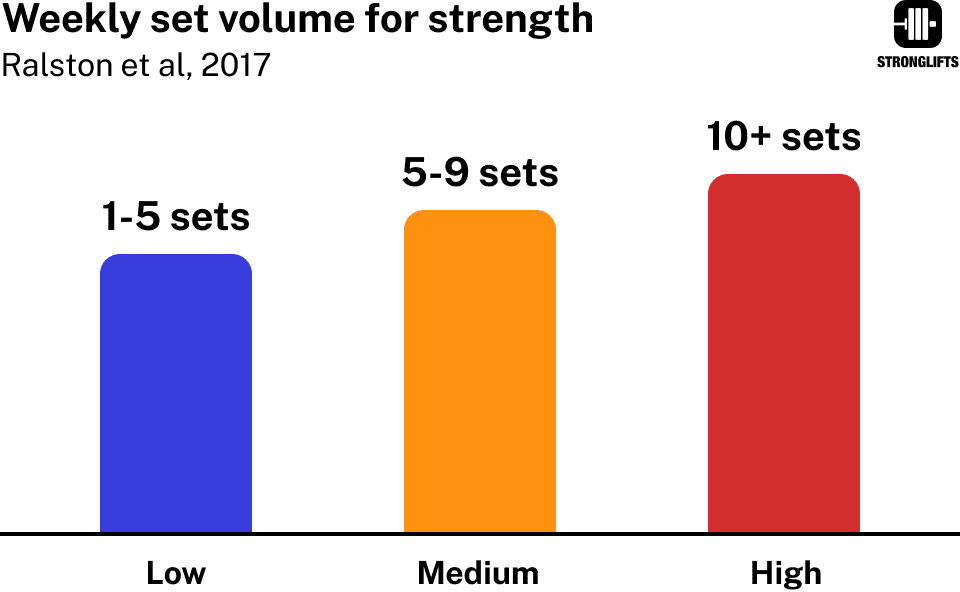

A study by Ralston et al found similar results (45). New lifters built stronger legs with three sets than one set. But three sets and one set resulted in similar strength gains for the upper body. However – for stronger lifters, three sets was superior to one set for the upper body too. They were more trained. Their upper body now needed more volume too.

This shows once again that what gets your bench from 0 to say 175lb may not get it to 250lb. Your body adapts. The same workout that worked great before may no longer provide a sufficient stimulus to increase your strength further. If you’re stuck on the Bench Press, you may just need to Bench more.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate increases the Bench volume and frequency. Check it out.

How to break plateaus

Reduce the Squat frequency

Start Squatting 2x/week instead of 3x/week. This slows down the progression and creates room for more Deadlifts.

Lifters new to Stronglifts 5×5 often don’t get why Squat is 5×5 3x/week while Deadlift is 1×5 every other workout. Why not do 5×5 Deadlifts too? Because that would be 25 sets per week for your legs alone. That’s too much volume for most people (46). It only works while the weights are still light as everyone who has attempted this quickly learns for themselves, the hard way.

Once you start Stronglifts 5×5 you discover that Deadlifts increase despite “only” doing 1×5. It’s not much practice. But as powerlifters would tell you, Deadlifts are less technical than Squats (37). The range of motion is shorter, each reps starts from the floor, less things can go wrong. The strength gains from Squats also carry over to Deadlifts (47). Both lifts work similar muscles. That’s why your Deadlift increases despite the low volume.

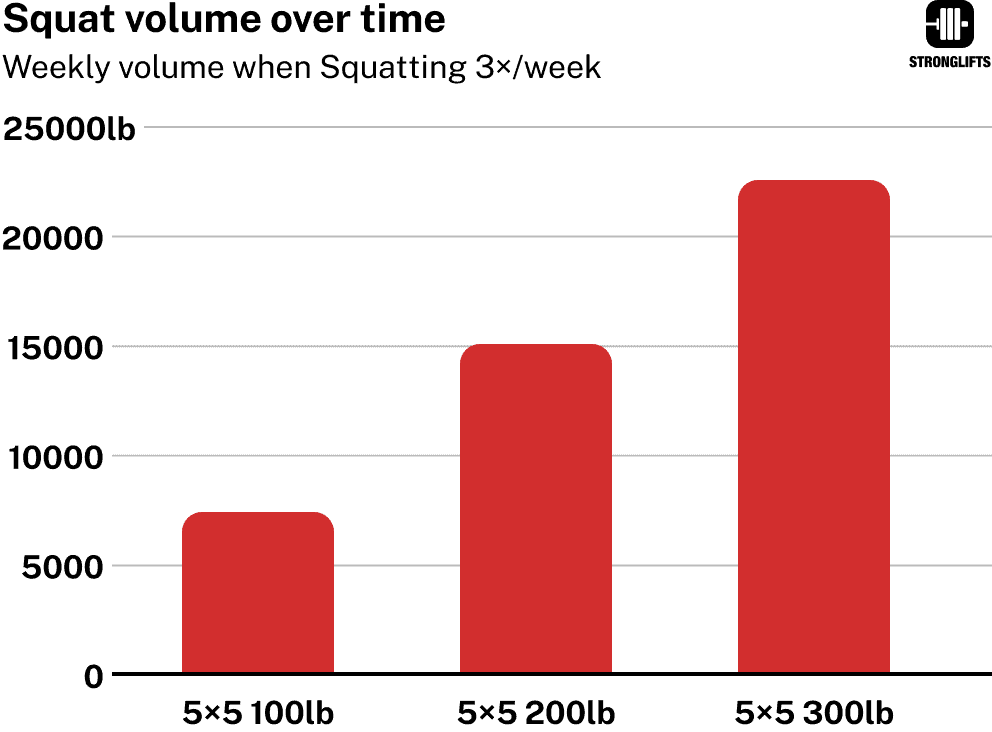

The problem is that Squatting 3x/week for 5×5 eventually becomes too much. Volume = set × rep × kg/lb. You start light and so the Squat volume is initially low. But you add weight over time. This slowly increases the volume.

Say you start Stronglifts 5×5 with 100lb on the Squat. Your weekly volume is about 7500lb (5x5x100 x 3 workouts). A few months later you Squat 300lb for 5×5. The volume in one Squat workout is now 7500lb – the same as what you did before in a whole week. Although you’re still doing 5×5 3x/week, your training volume is higher because the weight on the bar has tripled. That’s why 5×5 Squats 3x/week become so hard after a while.

Switching to 2x/week Squats makes things easier. It also creates room for 5×5 Deadlifts 1x/week. But isn’t 2x/week Squats still too much for sustainable progress? Absolutely. That’s why we’re going to use variations…

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate uses a reduced Squat frequency. Check it out.

Add exercise variety

What do you think works best for breaking plateaus?

- Changing exercises; OR

- Changing reps; OR

- Changing both?

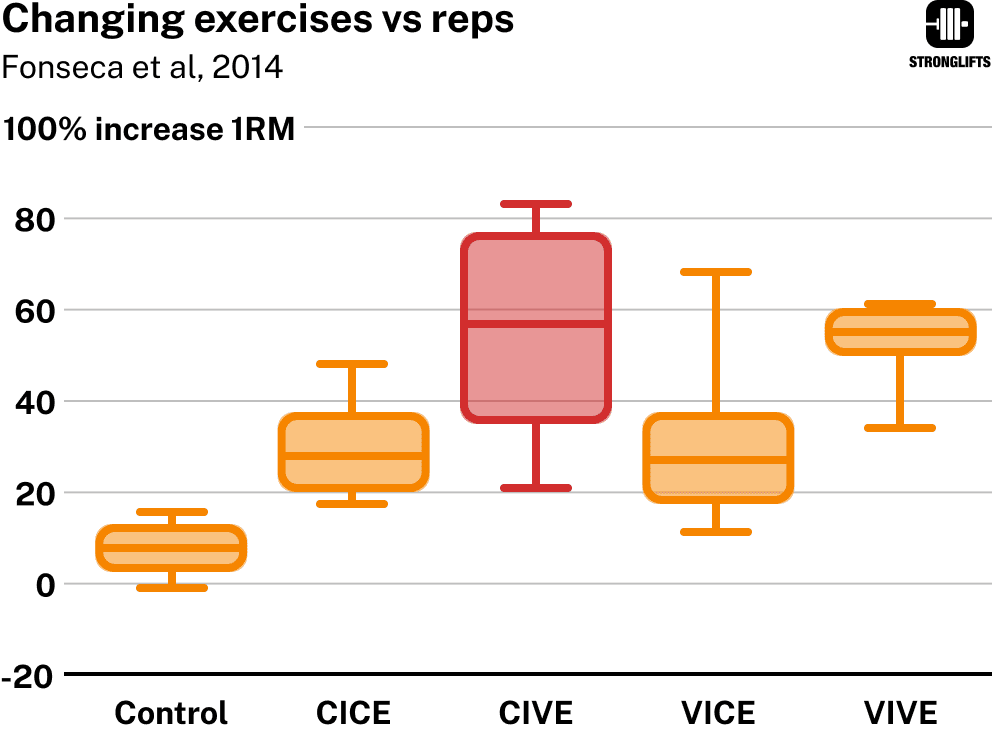

A study by Fonseca et al compared changing exercises and changing reps for increasing strength on the Squat (48). 49 lifters were divided into five groups (including one control not listed below). Their average Squat was +110kg or ~240lb. These are the workouts the four groups did 2x/week…

| Fonseca et al, 2014 | Week 1-4 | Week 5-8 | Week 9-12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CICE | Squat 4×8 | Squat 6×8 | Squat 9×8 |

| CIVE | Squat 2×8 Leg Press 2×8 | Squat 3×8 Deadlift 3×8 | Squat 3×8 Deadlift 3×8 Lunges 3×8 |

| VICE | Squat 2×6, 2×10 | Squat 2×6, 2×8, 2×10 | Squat 3×6, 3×8, 3×10 |

| VIVE | Squat 3×6/10/6 Leg Press 1×10 | Squat 3×6/8/10 Deadlift 3×6/8/10 | Squat 3×6/8/10 Deadlift 3×6/8/10 Lunges 3×6/8/10 |

Guess who increased their Squat more…

The CIVE group that changed exercises but didn’t change reps gained more strength on the Squat. Changing exercises was more effective than changing reps for increasing strength.

Here’s what’s interesting:

- The VICE group that used different reps (6, 8 and 10) didn’t gain more strength than the CICE group that always did the same reps (8 only).

- The VIVE group that changed exercises and reps gained less strength than the CIVE group that only changed exercises. The researchers thought that keeping the reps constant may have helped the CIVE group to better focus on improving their form.

My take? We know that variety is a fundamental principle of progress (41, 42). The old-time lifters always talked about the importance of “switching things up to confuse your muscles”. So what confuses you more? Doing 2×6 and 2×10 instead of 4×8? Or doing Squats, Leg Press and Lunges instead of only Squats? From my experience, varying the exercises is a bigger change. This may be why it works better for increasing strength.

Here’s another idea that I picked up from my coach Mike Tuchscherer. Many people stop paying attention when they do the same exercise over and over for months. Before they focused on improving their form. Now they’re simply going through the motions. Their technique doesn’t improve because there’s no challenge anymore. They’ve become complacent in their comfort zone. Introducing exercise variations can impose new challenges and bring the attention back. This can unlock new strength gains.

So instead of doing Squat, Squat, Squat 3x/week, start alternating Squats with Squat-like exercises. Here’s a simple example…

| Monday | Wednesday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Squat 5×5 | Squat 5×5 | Squat 5×5 |

| Now | Squat 5×5 | Deadlift 5×5 | Pause Squat 5×5 |

You’re still Squatting 2x/week. But you’re now alternating Squats with Pause Squats. Here’s how this helps you break plateaus and get stronger…

- Slower progression. The weights now increase once a week on each lift. If you get small plates and go up by 2.5lb/week, you add 130lb or ~60kg/year. Your progress is now more sustainable.

- More frequent PRs. Each Squat exercise progresses independently. You get two chances to hit personal records (PRs). This is more fun than repeating the same Squat 2x/week without seeing progress.

- Improved form. Say you struggle to Squat deep enough. The Pause Squat makes you spend more time in the bottom. This strengthens that position while improving flexibility. It carries over to better Squat form.

- Injury prevention. Some people get wrist or elbow pain from Squatting heavy 3x/week. Using Squat variations gives those joints a break from repetitive stress. It also forces you to go lighter in some workouts while still training hard. You’ll lift less weight on Pause Squats due to the pause in the bottom. This reduces the risk of overuse injuries.

People often want to know how I train since I’ve outgrown Stronglifts 5×5. This is it. I still Squat several times a week after all those years. But I don’t do the same Squat every workout anymore. I use variations all the time. Props to my coach Mike Tuchscherer. He taught me this several years ago.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate uses exercise variety. Check it out.

Add Bench volume

If you’re plateauing on your Bench Press, start doing more bench. The Bench volume on Stronglifts 5×5 is sufficient when you start lifting. But once you hit plateaus, you need to increase the volume in order to progress further.

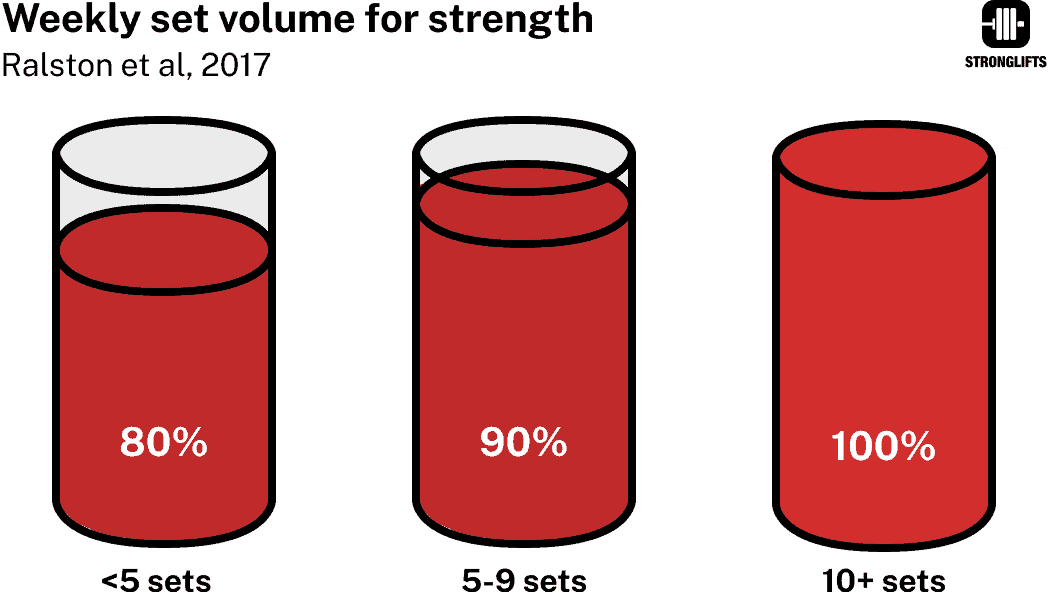

A study by Ralston et al analyzed how many sets per week you need to do per exercise to increase strength (46). Here’s what they found…

+10 sets/week/exercise is high volume. The study called this “marginally more effective in producing strength gains” than low volume (46). The first sets yield most of the gains. Extra sets result in diminishing returns. Many beginners think that doing double the volume means double the gains. But the study found that high volume is only about 20% extra gains.

Note that the appropriate volume depends on your experience. New lifters need less volume than experienced ones as explained here. Here’s the amount of volume the study recommends to do…

| Ralston et al, 2017 | Recommended volume |

|---|---|

| Beginners | Medium |

| New lifters | Medium |

| Time-limited | Medium |

| Trained lifters | Medium to high volume |

This once again shows that the same workouts that increase your bench at first may not increase it once you get stronger. As your body changes, so do your workouts have to change over time. Spending 30min in the sun may be enough to develop a tan if you’re pale from sitting inside for years. But once your skin has become darker, you’ll need to spend more than 30min/day in the sun if you want to further deepen your tan. Same idea here.

Stronglifts 5×5 is a program aimed at new or returning lifters. Let’s check how much volume it has by counting the weekly sets. Exercises like Bench Press alternate each workout. You Bench twice in the A/B/A weeks but once in the B/A/B weeks. We’ll take the average to calculate the weekly sets.

| Exercise | Weekly sets | Volume |

|---|---|---|

| Squat | 15 sets | High |

| Bench Press | 7.5 sets | Medium |

| Overhead Press | 7.5 sets | Medium |

| Barbell Row | 7.5 sets | Medium |

| Deadlift | 1.5 sets | Low |

Stronglifts 5×5 is medium volume for Bench, Overhead Press and Rows. It’s high volume for Squats (read why here and here). This compensates for the low Deadlift volume as both lifts work similar muscles. 15 sets may seem like a lot, but new lifters need more volume for legs (read why here)

By the way, notice how Stronglifts 5×5 has more volume for your upper than lower body. Some people think it’s more lower body focused because you Squat 3x/week. But it’s actually more upper body focused.

| Stronglifts 5×5 | Weekly sets | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Upper body | 22.5 sets | 58% |

| Lower body | 16.5 sets | 42% |

Strength = skills × muscle. So let’s also look at the number of weekly sets for your major muscle groups. We want those muscles to get bigger as this helps us lift more weight. It turns out that the volume definitions for hypertrophy and strength are similar (49, 46). Here’s the weekly set volume per muscle group on Stronglifts 5×5…

| Muscle | Weekly sets | Exercise | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legs | 16.5 | Squat, Deadlift | High |

| Shoulders | 15 | Bench, OHPress | High |

| Triceps | 15 | Bench, OHPress | High |

| Back | 9 | Row, Deadlift | Medium |

| Biceps | 7.5 | Row | Medium |

| Chest | 7.5 | Bench | Medium |

Here’s what we learn from all of this:

- The volume for legs coming from Squats and Deadlift is 16.5 sets per week. That’s high volume. Most people who plateau on Stronglifts 5×5 don’t want more leg work. The volume is enough already. They just want a more sustainable progression. We’ve already fixed that by lowering the Squat frequency and introducing variations.

- Your shoulders and triceps each get 15 sets per week from the Bench Press and Overhead Press. Those muscles are prime movers on the Bench and so they’re important. 15 sets is high volume. And so those muscles are already getting plenty of work to progress.

- Your biceps get 7.5 sets per week from Rows. That’s medium volume. But you’ve probably added assistance work like chinups and curls. So you’re likely doing high volume for biceps already.

- Your chest gets 7.5 sets per week from Bench. This is medium volume and enough when starting out as a new lifter. However, once you start plateauing, this needs to increase to high volume.

If you’re plateauing on your Bench Press, you need to start Benching more. You need to increase your Bench volume. You need to particularly increase the amount of work for your chest. And you need to start giving the Bench priority over the Overhead press. This will help you further increase your Bench while also adding size to your chest.

Stop alternating Bench and Overhead Press every workout. Start benching three times a week like powerlifters do (4, 50). Use exercise variations to slow down the progression at the same time. Here’s an example…

| Monday | Wednesday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Bench 5×5 | Overhead Press 5×5 | Bench 5×5 |

| Now | Bench 5×5 | Incline Bench 5×5 | Pause Bench 5×5 |

Let’s count the volume now…

| Bench Press | Before | Now |

|---|---|---|

| Weekly sets | 7.5 | 15 |

| Volume | Medium | High |

| Frequency | 1.5x/week | 3x/week |

You’re now doing the Bench Press 3x/week for a total of 15 sets. Here’s how this helps you break plateaus and get stronger…

- More volume. 7.5 sets/week is medium volume. That’s enough to progress on Bench when you start Stronglifts 5×5. But you’re stronger now. 15 sets is high volume and helps you progress further.

- More practice. Before you did Bench Press in workout A only. This meant that you practiced once every 4-5 days or 6x/month. Now you Bench Press 3x/week. That’s 12x/month or double the practice than before. This helps you improve your form further.

- Slower progress. The weights increase once a week on each Bench exercise. If you get small plates and add 1lb/week, you increase by 52lb or ~24kg/year. Your progress is more sustainable.

- More frequent PRs. Each Bench exercise progresses independently. You get three chances to hit personal records (PRs). This is more fun than doing the same Bench 2-3x/week without seeing progress.

- Injury prevention. Some people’s shoulders can’t take 3x/week flat bench. Variations give your joints a break from repetitive stress (51). You may be surprised to find out that you can Bench 3x/week if you don’t do the same flat bench all the time but use variations. They load your joints differently and force you to use a lighter weight.

Where does the Overhead Press fit into all of this? You can still do it as an assistance exercise after your Bench Press.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate increases the Bench Press volume. Check it out.

Frequently asked questions

When should you make these changes?

Many people want to know the exact weight they need to reach before making changes. But there’s no such thing.

Different people will progress at different rates because of their individual situations. Even identical twins of the same age and genetics may need to modify the same training program at different times if one prioritizes nutrition and recovery while the other neglects those factors.

Instead, look at your progress and listen to your body. If you haven’t been able to progress for several weeks, if you’re not as motivated as you used to be, if you’re dreading all the Squats, then make changes. Simple.

Note: Stronglifts 5×5 Intermediate implements all the changes needed to help you break through plateaus. Check it out.

What if you plateau on Bench Press but not Squat and Deadlift?

Start Benching every workout. Use variations. Example…

- Workout A: Squat, Bench Press, Barbell Row

- Workout B: Squat, Pause Bench, Deadlift

This increases your Bench Press volume from 7.5 sets to 15 sets per week. Overhead Press moves to assistance work in workout B after Deadlifts.

Your progression will still be too fast since you’ll add weight 2x/week. Slow it down by microloading – add 2.5lb or less per workout. You can repeat the weight for two or three workouts before going up in weight. Make sure you switch from 5×5 straight sets to top/back off sets.

The Overhead Press can move to assistance work.

What if you plateau on Overhead Press but not Squat and Deadlift?

Focus on the Bench Press. Start benching every workout as explained above. Move the Overhead Press to assistance work.

The Bench Press is easier to progress on than the Overhead Press. It uses more muscles – not just your shoulders and triceps but also your chest. That’s why the world records are higher on the Bench Press. Focusing on the Bench Press makes it easier to strengthen the same muscles that you use on the Overhead Press. Those strength gains will carry over.

You can replace the Overhead Press by a variation to get a change of pace. This can be the Dumbbell Overhead Press, Push Press, Seated Overhead Press, or any other vertical press compound exercise that you like. Do that lift for a while, continue to get stronger on the Bench Press, then come back to Overhead Press in a few weeks. You’ll be stronger by then.

Is lifting more weight always progress?

NOTE: read this for context.

Lifting more weight doesn’t always mean progress.

Say you lift 200lb for 5×5. Your average RPE is 8. That’s an estimated one rep max of 246.5lb. Next workout you do 5×5 205lb. Your average RPE is 9 this time. Your estimated one rep max is now 245lb. In this case you didn’t get stronger. You simply lifted a weight closer to your limit.

So why did I say that lifting more weight is progress, regardless of how much harder it may have felt? Because some people don’t understand that hard work is required to progress. The program starts light. Not that much effort is needed during the first weeks to progress. Light weights can be lifted with little effort. But heavy weights cannot. And so your level of effort needs to increase as you add weight on the bar. You need to work harder.

Think of it this way. Let’s say your best Bench Press is 200lb. Can you lift the same weight if you keep your feet in the air? No, because that takes your legs out of the movement. Yet you can bench your warmup weight, say 135lb, with your feet in the air. This shows how you can’t lift a heavy weight like a light weight. The heavy weight requires more effort – in this case, using every muscle that you possibly can, including your legs.

The heavier the weight, the greater the effort you need to put in. If this sounds tiring, it is. But it gets easier over time. You get used to working hard.

Join the Stronglifts community to get free access to all the spreadsheets for every Stronglifts program. You’ll also get daily email tips to stay motivated. Enter your email below to sign up today for free.

References

1. Schoenfeld, Brad J. “The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 24,10 (2010): 2857-72.

2. Latella, Christopher et al. “Long-Term Strength Adaptation: A 15-Year Analysis of Powerlifting Athletes.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 34,9 (2020): 2412-2418.

3. Appleby, Brendyn et al. “Changes in strength over a 2-year period in professional rugby union players.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 26,9 (2012): 2538-46.

4. Androulakis-Korakakis, Patroklos et al. “The Minimum Effective Training Dose Required for 1RM Strength in Powerlifters.” Frontiers in sports and active living vol. 3 713655. 30 Aug. 2021.

5. “Powerlifting Records.” Powerlifting Rankings, www.openpowerlifting.org/records/raw/ipf.

6. Ball, Robert, and Drew Weidman. “Analysis of USA Powerlifting Federation Data From January 1, 2012-June 11, 2016.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 32,7 (2018): 1843-1851.

7. Janssen, I et al. “Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr.” Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) vol. 89,1 (2000): 81-8.

8. Miller, A E et al. “Gender differences in strength and muscle fiber characteristics.” European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology vol. 66,3 (1993): 254-62.

9. “Technical Rules.” International Powerlifting Federation IPF – International Powerlifting Federation IPF, https://www.powerlifting.sport/rules/codes/info/technical-rules.

10. “List of World Records in Olympic Weightlifting.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_world_records_in_Olympic_weightlifting#Men_(1920%E2%80%931972).

11. Kilgore, Lon. “Weightlifting Performance Standards.” ExRx.net, https://exrx.net/Testing/WeightLifting/StrengthStandards

12. Gleason, Benjamin H et al. “Troubleshooting a Nonresponder: Guidance for the Strength and Conditioning Coach.” Sports (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 9,6 83. 5 Jun. 2021.

13. Jäger, Ralf et al. “International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition vol. 14 20. 20 Jun. 2017.

14. Slater, Gary John et al. “Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training.” Frontiers in nutrition vol. 6 131. 20 Aug. 2019, doi:10.3389/fnut.2019.00131

15. Kirschen, Gregory W et al. “The Impact of Sleep Duration on Performance Among Competitive Athletes: A Systematic Literature Review.” Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine vol. 30,5 (2020): 503-512.

16. Halson, Shona L. “Nutrition, Sleep and Recovery.” European Journal of Sport Science, vol. 8, no. 2, 2008, pp. 119-126.

17. Dupuy, Olivier et al. “An Evidence-Based Approach for Choosing Post-exercise Recovery Techniques to Reduce Markers of Muscle Damage, Soreness, Fatigue, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in physiology vol. 9 403. 26 Apr. 2018.

18. Bartholomew, John B et al. “Strength gains after resistance training: the effect of stressful, negative life events.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 22,4 (2008): 1215-21.

19. Miranda, Humberto et al. “Effect of two different rest period lengths on the number of repetitions performed during resistance training.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 21,4 (2007): 1032-6.

20. Willardson, Jeffrey M, and Lee N Burkett. “A comparison of 3 different rest intervals on the exercise volume completed during a workout.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 19,1 (2005): 23-6.

21. Headley, Samuel A et al. “Effects of lifting tempo on one repetition maximum and hormonal responses to a bench press protocol.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 25,2 (2011): 406-13.

22. Schoenfeld, Brad J et al. “Effect of repetition duration during resistance training on muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 45,4 (2015): 577-85.

23. Pratt, Jedd et al. “Forearm electromyographic activity during the deadlift exercise is affected by grip type and sex.” Journal of electromyography and kinesiology : official journal of the International Society of Electrophysiological Kinesiology vol. 53 (2020): 102428.

24. Gomo, Olav, and Roland Van Den Tillaar. “The effects of grip width on sticking region in bench press.” Journal of sports sciences vol. 34,3 (2016): 232-8.

25. Gantois, Petrus et al. “Mental Fatigue From Smartphone Use Reduces Volume-Load in Resistance Training: A Randomized, Single-Blinded Cross-Over Study.” Perceptual and motor skills vol. 128,4 (2021): 1640-1659.

26. P. Fisher, James, et al. “Periodization for optimizing strength and hypertrophy; the forgotten variables.” Journal of Trainology, vol. 7, no. 1, 2018, pp. 10-15.

27. Mazzetti, S A et al. “The influence of direct supervision of resistance training on strength performance.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 32,6 (2000): 1175-84.

28. Sheridan, Andrew et al. “Presence of Spotters Improves Bench Press Performance: A Deception Study.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 33,7 (2019): 1755-1761.

29. Hostler, D et al. “The effectiveness of 0.5-lb increments in progressive resistance exercise.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 15,1 (2001): 86-91.

30. Keogh, Justin W L et al. “Can absolute and proportional anthropometric characteristics distinguish stronger and weaker powerlifters?.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 23,8 (2009): 2256-65.

31. Taber, Christopher B et al. “Exercise-Induced Myofibrillar Hypertrophy is a Contributory Cause of Gains in Muscle Strength.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 49,7 (2019): 993-997.

32. Brechue, William F, and Takashi Abe. “The role of FFM accumulation and skeletal muscle architecture in powerlifting performance.” European journal of applied physiology vol. 86,4 (2002): 327-36.

33. Katch, V L et al. “Muscular development and lean body weight in body builders and weight lifters.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 12,5 (1980): 340-4.

34. D’Souza, Randall F et al. “MicroRNAs in Muscle: Characterizing the Powerlifter Phenotype.” Frontiers in physiology vol. 8 383. 7 Jun. 2017.

35. Deschenes, Michael R, and William J Kraemer. “Performance and physiologic adaptations to resistance training.” American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation vol. 81,11 Suppl (2002): S3-16.

36. Leaf, Alex, and Jose Antonio. “The Effects of Overfeeding on Body Composition: The Role of Macronutrient Composition – A Narrative Review.” International journal of exercise science vol. 10,8 1275-1296. 1 Dec. 2017

37. Pritchard, Hayden J et al. “Tapering Practices of New Zealand’s Elite Raw Powerlifters.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 30,7 (2016): 1796-804.

38.Travis, S Kyle et al. “Characterizing the Tapering Practices of United States and Canadian Raw Powerlifters.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 35,Suppl 2 (2021): S26-S35.

39. Pritchard, Hayden, et al. “Effects and Mechanisms of Tapering in Maximizing Muscular Strength.” Strength & Conditioning Journal, vol. 37, no. 2, 2015, pp. 72-83.

40. Mattocks, Kevin T et al. “Practicing the Test Produces Strength Equivalent to Higher Volume Training.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 49,9 (2017): 1945-1954.

41. Kraemer, William J, and Nicholas A Ratamess. “Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 36,4 (2004): 674-88.

42. American College of Sports Medicine. “American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults.” Medicine and science in sports and exercise vol. 41,3 (2009): 687-708.

43. Rønnestad, Bent R et al. “Dissimilar effects of one- and three-set strength training on strength and muscle mass gains in upper and lower body in untrained subjects.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 21,1 (2007): 157-63.

44. Wernbom, Mathias et al. “The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 37,3 (2007): 225-64.

45. Ralston, Grant W et al. “Re-examination of 1- vs. 3-Sets of Resistance Exercise for Pre-spaceflight Muscle Conditioning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in physiology vol. 10 864. 24 Jul. 2019.

46. Ralston, Grant W et al. “The Effect of Weekly Set Volume on Strength Gain: A Meta-Analysis.” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 47,12 (2017): 2585-2601.

47. Nigro, Federico, and Sandro Bartolomei. “A Comparison Between the Squat and the Deadlift for Lower Body Strength and Power Training.” Journal of human kinetics vol. 73 145-152. 21 Jul. 2020.

48. Fonseca, Rodrigo M et al. “Changes in exercises are more effective than in loading schemes to improve muscle strength.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 28,11 (2014): 3085-92.

49. Schoenfeld, Brad J et al. “Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of sports sciences vol. 35,11 (2017): 1073-1082.

50. Travis, S Kyle et al. “Characterizing the Tapering Practices of United States and Canadian Raw Powerlifters.” Journal of strength and conditioning research vol. 35,Suppl 2 (2021): S26-S35.

51. Saeterbakken, Atle Hole et al. “The Effects of Bench Press Variations in Competitive Athletes on Muscle Activity and Performance.” Journal of human kinetics vol. 57 61-71. 22 Jun. 2017.